With the beginning of summer, many individuals will start up their barbecues and cook everything from wieners to steaks. Millions of Americans who are allergic to seafood won’t be able to eat shrimp, but a method that was published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry might change that. According to the researchers, reverse-pressure sterilization can result in a shrimp product that is less allergenic and does not cause severe reactions in mice that are sensitive to crustaceans.

Dairy products, wheat, peanuts, seafood, and other foods are some of the most common foods that people are allergic to. The safe framework confuses a few proteins from these food sources with an interloper and dispatches a reaction against them. In minor cases, this can cause some uneasiness or enlargement, and in extreme cases, it tends to undermine life. However, the proteins that the immune system reacts to can change or break down when food is heated, making it safer for people with allergies to eat the food because antibodies might not be able to recognize the proteins.

Some studies on oysters and other shellfish have shown that roasting actually increases allergenicity, while others have shown that it decreases it. Along these lines, Na Sun and partners needed to see precisely the way in which allergens in shrimp change during post-handling. Additionally, they wanted to see if they could develop a product that was less allergenic.

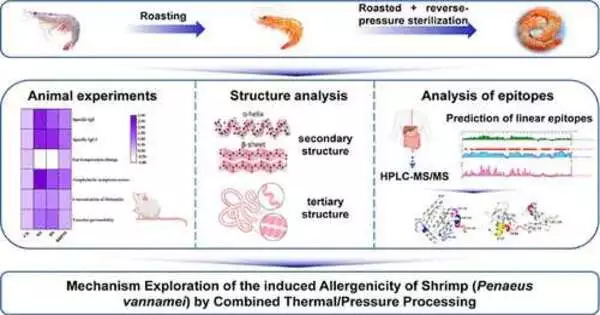

The team divided shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) samples into three groups. The first group was roasted, while the second was raw. After roasting the third group, the crustaceans underwent reverse-pressure sterilization, in which they were subjected to high pressure and steam. Each of the three groups was given to a separate group of mice with a shrimp allergy after being mashed into pastes.

Credit: The Journal of Food and Agricultural Chemistry, DOI: 10.1021/acs.jafc.3c01557

Both the crude and cooked shrimp caused comparative responses, including expanded degrees of receptor and harm to the spleen and lungs, suggesting that simmering alone didn’t change the protein’s properties much. Organ damage and reactions were less severe in the third group.

The team discovered that roasting changed the shape of the allergen proteins in the shrimp samples but that antibodies could still bind to them. However, the proteins became clumped together during reverse-pressure sterilization, concealing the binding sites. This blocked antibodies from hooking on and consequently forestalled an extreme, unfavorably susceptible response.

According to the researchers, this method was able to successfully and effectively reduce the shrimp’s allergenicity and reveal the specific protein changes that caused it.

More information: Kexin Liu et al, Reduced Allergenicity of Shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) by Altering the Protein Fold, Digestion Susceptibility, and Allergen Epitopes, Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry (2023). DOI: 10.1021/acs.jafc.3c01557