Severe flooding occurs as a result of atmospheric conditions that cause heavy rain or rapid melting of snow and ice. Flooding can also be caused by geography. Areas near rivers and cities, for example, are frequently prone to flash floods. Floods are now a worldwide disaster; this month alone, floods have claimed the lives of people in the United States, Africa, South America, and Europe.

The University of Queensland researchers used radar imaging sensors on satellites to see through clouds and map flooding, and they believe the technique could provide faster, more detailed information to keep communities safe. According to Professor Noam Levin of the University of Queensland’s School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, the project combined images from optical satellites with data from imaging radar satellites.

A flood is an overflow of water onto normally dry land. Flooding can occur almost anywhere. They can cover an area with a few inches of water or bring enough water to cover a house’s roof. Floods can be dangerous to communities because they can last for days, weeks, or even months.

Monitoring floods in towns and cities is challenging, with flood waters often rising and then receding in a few days. While large satellites in the past provided images every 7-14 days, now groups of small satellites can collect several images a day over the same location.

Professor Levin

Monitoring floods in towns and cities is challenging, with flood waters often rising and then receding in a few days,” Professor Levin said. “While large satellites in the past provided images every 7-14 days, now groups of small satellites can collect several images a day over the same location.

“Radar imaging sensors can provide images at night or on days with thick cloud cover – a huge advantage in stormy conditions. They use a flash, like on a camera, and the light is sent at wavelengths between 1mm and 1.0m, which can pass through clouds and smoke.”

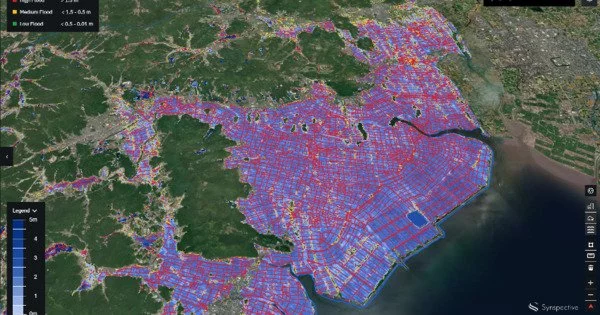

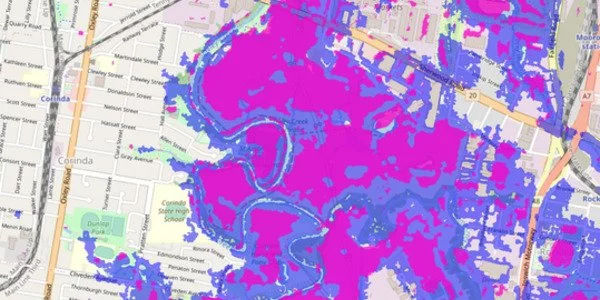

During Brisbane’s February 2022 floods, researchers combined satellite day-time pictures showing the extent of the flood with imaging radar and optical night-time data of the lights associated with human activity.

“We could see which areas became dark as the flood waters encroached,” Professor Levin said. “We matched this with data from river gauges operated by the Bureau of Meteorology, and with changes in electricity loads reported by Energex, the power supplier.”

Professor Stuart Phinn said the technique could play a vital role in protecting Australians during future flooding events. “In combination with existing flood monitoring and modelling technologies, satellites could change the way we monitor major flood events, understand how they occur, and direct emergency and other responses,” Professor Phinn said.

Flooding can also be influenced by geography. Floods, for example, are common in areas near rivers. Rooftops funnel rainfall to the ground below, and paved surfaces such as highways and parking lots prevent the ground from absorbing the rain, making urban areas more vulnerable to flooding.

“Agencies monitoring the floods can assess changes and alert people in at-risk areas with faster update times – at least twice a day – and more accurate and timely data. This technique can also be used after a disaster to determine the extent of damage, direct recovery efforts, and evaluate insurance claims.”