As indicated by another review, a wiped-out reptile’s strangely formed chompers, fingers, and ear bones might tell us a lot about the versatility of life on the planet.

Truth be told, scientists at Yale, Sam Houston State College, and the College of the Witwatersrand say the 250-million-year-old reptile, known as Palacrodon, fills in a significant hole in how we might interpret reptile development. It’s likewise a sign that reptiles, plants, and environments might have fared better or recuperated all the more rapidly than recently thought after a mass termination occasion cleared out the greater part of the plant and creature species in the world.

“We currently realize that Palacrodon comes from one of the last heredities to diverge the reptile tree of life before the development of present day reptiles,” said Kelsey Jenkins, a doctoral understudy in Yale’s Division of Earth and Planetary Sciences in the Staff of Expressions and Sciences and the first creator of the review, which shows up in the Diary of Life systems. “We additionally realize that Palacrodon lived directly following the most decimating mass elimination in Earth’s set of experiences.”

“Palacrodon’s peculiar teeth, as well as a few other specialized aspects of its anatomy, suggest it was either herbivorous or interacted with plant life in some way. This indicates the early recovery of plants, and, more broadly, the recovery of ecosystems after the mass extinction.”

Kelsey Jenkins, a doctoral student in Yale’s Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences

That would be the Permian-Triassic annihilation event, which happened quite a while back. Known as “the Incomparable Kicking the Bucket,” it killed off 70% of earthly species and 95% of marine species.

Although an enormous number of reptile species at last returned from this termination occasion, the subtleties of how that happened are cloudy. Scientists have gone through many years attempting to fill in the holes in how we might interpret key transformations that empowered reptiles to thrive after the Permian-Triassic annihilation — and what those variations might uncover about the environments where they resided.

Jenkins said Palacrodon might assist with addressing a portion of those inquiries.

On the whole, she and her partners needed to get a superior glance at the little reptile.

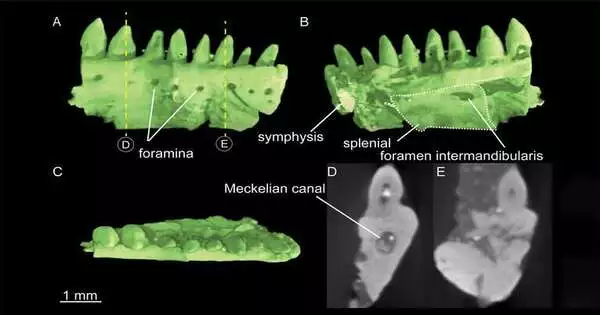

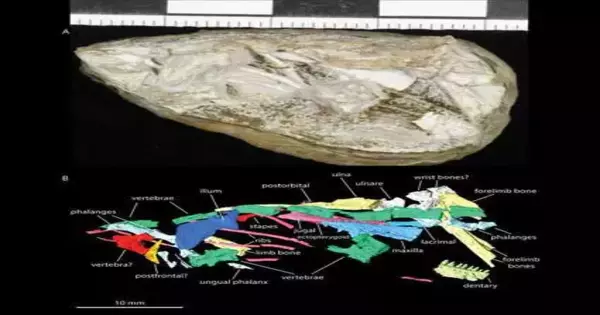

An example of Palacrodon (top) from Antarctica and a CT check (lower part) of the example. Up to this point, what we had had some significant awareness of Palacrodon came from assessments of cranial pieces from fossils tracked down in South Africa and Arizona. The data gathered from those fossils was so restricted, nonetheless, that Palacrodon was avoided with regard to most logical investigations of reptilian development.

Jenkins and her colleagues — including co-creator Bhart-Anjan S. Bhullar, right-hand professor of Earth and planetary science at Yale and an associate keeper at the Yale Peabody Gallery of Natural History — discovered another scientific way to deal with bears in looking at Palacrodon for the new review.

In particular, they utilized processed tomographic (CT) checking and microscopy to dissect the most ridiculously complete Palacrodon example, a fossil from Antarctica. Bhullar’s lab at Yale is especially known for its imaginative utilization of CT examining and microscopy to make 3D pictures of fossils. (Jenkins and Bhullar likewise accomplished field work in South Africa and the southwestern U.S., connecting with Palacrodon.)

Involving the innovation for this review, the scientists had the option to get attributes of the reptile’s teeth, as well as other actual highlights. They said that Palacrodon’s teeth were the most appropriate for crushing plant material and that the reptile was probably able to do this sporadically by climbing or sticking onto vegetation.

“Palacrodon’s uncommon teeth, and a couple of other particular highlights of its life structures, show it was logically herbivorous or connected with vegetation here and there,” Jenkins said. “This signals the early bounce back of plants, and all the more comprehensively, the bounce back of environments following this mass elimination.”

Jenkins said the review focuses on a requirement for additional assessment of fossils from the time span soon after the Permian-Triassic eradication event.

More information: Kelsey M. Jenkins et al, Re‐description of the early Triassic diapsid Palacrodon from the lower Fremouw formation of Antarctica, Journal of Anatomy (2022). DOI: 10.1111/joa.13770