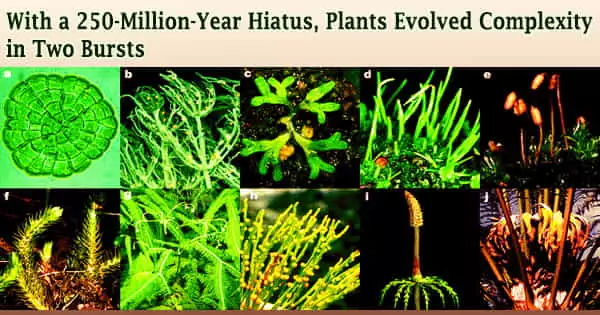

Rather than evolving over hundreds of millions of years, land plants underwent considerable diversity in two 250 million-year bursts, according to a Stanford-led study.

The first occurred early in plant history, giving rise to the creation of seeds, and the second took place during the diversity of flowering plants. Plant complexity is classified using a unique yet simple metric based on the arrangement and number of basic elements in their reproductive mechanisms.

Scientists have long assumed that plants got increasingly complex with the introduction of seeds and blooms, but the latest results, published in Science on September 17, 2021, add light on the timing and scale of those changes.

“The most surprising thing is this kind of stasis, this plateau in complexity after the initial evolution of seeds and then the total change that happened when flowering plants started diversifying,” said lead study author Andrew Leslie, an assistant professor of geological sciences at Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences (Stanford Earth). “The reproductive structures look different in all these plants, but they all have about the same number of parts during that stasis.”

An unusual comparison

Flowers are unlike any other plant group in that they produce a wide range of colors, scents, and shapes that nourish animals and thrill the senses. They’re also complex: petals, anthers, and pistils are intertwined in exact patterns to entice pollinators and deceive them into distributing pollen from one flower to the next.

Insect pollination and animal seed dispersal may have appeared as early as 300 million years ago, but it’s not until the last 100 million years that these really intricate interactions with pollinators are driving this super high complexity in flowering plants. There was such a long period of time where plants could have interacted with insects in the way that flowering plants do now, but they didn’t to the same degree of intricacy.

Andrew Leslie

Scientists find it difficult to compare flowering plants to plants with simpler reproductive systems, such as ferns and some conifers, because of their intricacy. As a result, botanists have long focused on traits within family groups, and non-flowering plants are often studied apart from their more complex flowering relatives.

Leslie and his co-authors overcome these disparities by devising a system that categorizes the number of different types of pieces in reproductive systems solely based on observation. Each species was given a score based on the number of different pieces it possesses and the degree to which those parts clustered. From roughly 420 million years ago to the present, they classified about 1,300 land plant species.

“This tells a pretty simple story about plant reproductive evolution in terms of form and function: The more functions the plants have and the more specific they are, the more parts they have,” Leslie said. “It’s a useful way of thinking about broad-scale changes encompassing the whole of plant history.”

From shrubs to blooms

Earth was a warmer environment with no trees or terrestrial vertebrate animals when land plants first evolved in the early Devonian, about 420 million to 360 million years ago. The tallest terrestrial organism was a 20-foot fungus that looked like a tree trunk, while arachnids like scorpions and mites roamed the land among small, patchy vegetation.

Huge changes happened in the animal kingdom after the Devonian: land animals gained larger bodies and more varied diets, insects diversified, and dinosaurs arrived, but plants didn’t witness a significant rise in reproductive complexity until they produced flowers.

“Insect pollination and animal seed dispersal may have appeared as early as 300 million years ago, but it’s not until the last 100 million years that these really intricate interactions with pollinators are driving this super high complexity in flowering plants,” Leslie said. “There was such a long period of time where plants could have interacted with insects in the way that flowering plants do now, but they didn’t to the same degree of intricacy.”

Earth looked more like Yosemite National Park sans the flowering trees and bushes during the Late Cretaceous period, which lasted around 100 to 66 million years ago.

According to Leslie, the second burst of complexity was more striking than the first, underscoring the unique nature of flowering plants. Plants like the passionflower, which can have 20 different types of components, more than twice as many as non-flowering plants, arose during this time period.

Leslie conducted part of the research on and around Stanford’s campus by simply taking apart local plants and counting their reproductive organs, which resulted in the classification of 472 living species. Except for mosses and a few early plants that lack supporting tissue for carrying water and minerals, the analysis covers all vascular land plants.

“One thing we argue in this paper is that this classification simply reflects their functional diversity,” Leslie said. “They basically split up their labor in order to be more efficient at doing what they needed to do.”

Study co-authors include Carl Simpson of the University of Colorado Museum of Natural History and Luke Mander of The Open University.