You are sitting at work in a gathering when your psyche begins to meander to somewhere else. Unexpectedly, you understand that the individual driving the gathering has posed you an inquiry that you had not heard. For what reason does this occur?

“You really dream for brief minutes many many times in a day, frequently only for a couple of moments all at once,” says scientist Anna Chambers at the Foundation of Fundamental Clinical Sciences at the College of Oslo.

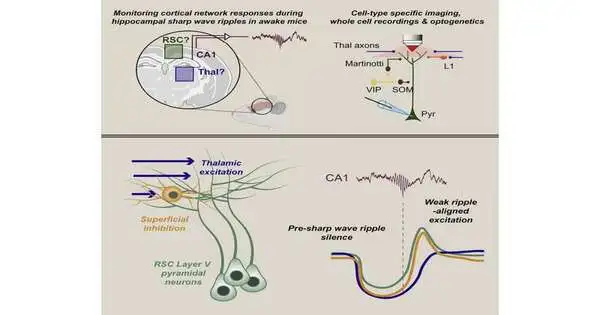

The clarification behind what occurs in our cerebrum when we dream arose when she and her examination group saw how long-haul recollections are put away. Inside the cerebrum, there is a 3-centimeter long, wiener-molded district called the hippocampus. It gets a great deal of data and impressions and is very significant for making recollections. Notwithstanding, after a specific measure of time has elapsed, the recollections evidently continue on. The group’s review, titled “Cell-type-explicit quietness in thalamocortical circuits goes before hippocampal sharp-wave swells,” was as of late distributed in Cell Reports.

“We observe that we are typically less conscious of what is going on around us while we are sleeping or in a state we refer to as “quiet wakefulness.” We can daydream or allow our thoughts to stray. The hippocampus sends electrical impulses that encode different memories when we are in this condition. Similar to how various barcodes help to specifically identify each item in a store,”

Associate Professor Koen Vervaeke at the Department of Molecular Medicine.

Chambers makes sense of that quite a while back, a patient had his hippocampus eliminated because of epilepsy. Without this piece of his cerebrum, he couldn’t shape new recollections. He would then fail to remember what had happened the other day, yet have no issue recollecting what had occurred before the activity.

The recollections from quite some time in the past were consequently put away in a better place in the cerebrum than in the hippocampus.

Your recollections are put away in another spot when you dream.

So how do recollections get to the region of the mind that manages long-haul stockpiling?

“We see that during rest and in a state we call ‘calm attentiveness,’ we are typically less mindful of what’s going on around us. We can fantasize or allow our brains to meander. At the point when we wind up in this express, the hippocampus sends electrical driving forces that encode different recollections. It is a piece like how different standardized tags extraordinarily distinguish an item in the store, “makes sense to academic administrator Koen Vervaeke at the Branch of Sub-atomic Medication.”

“This happens a large number of times each day without us monitoring it. So, in any event, when we assume we are not doing anything valuable, our cerebrum is exceptionally caught up with putting away new recollections after some time, “he adds.

The specialists accept that this permits you to recall where you grew up or went to class. Generally speaking, you can picture where you got hitched.

“You most likely recall these spots so well that you can draw a guide of the roads of the city, or of the rooms in the structure where you resided,” Chambers said.

The hippocampus sends feeble messages about past recollections to the remainder of the mind.

The examination group led tests, including mice, to investigate what happens when your brain meanders. They utilized unique magnifying instruments to gauge the movement of nerve cells from numerous regions of the mind all the while.

“We found that during calm attentiveness, the hippocampus just sends frail messages about past recollections to the remainder of the cerebrum. so frail that these messages are lost in the messiness of data that the remainder of the cerebrum encounters. This tracking down prompted the following inquiry: “How could the mind hear this murmuring from the hippocampus?” Christoffer Nerland Berge is a doctoral candidate.

The cerebrum becomes more settled, so it can all the more likely hear what the hippocampus is attempting to say.

The analysts, likewise, saw something different. One to two seconds before the hippocampus murmurs a memory, huge pieces of the mind become quiet. It is conceivable that this happens so different pieces of the cerebrum can more readily hear what the hippocampus is attempting to say.

“This makes sense of how recollections are moved from the hippocampus to different regions of the cerebrum where they are at last put away. At the point when we are alert, however separated—maybe staring off into space—we are less mindful of the occasions that are occurring around us. Our exploration shows that this occurs justifiably. The cerebrum is caught up in paying attention to recollections, all things considered, “says Chambers.

A few guardians think they need to engage their youngsters constantly.

“With the new discoveries, we figure you should be exhausted and that this is great for framing recollections,” Vervaeke says.

More information: Anna R. Chambers et al, Cell-type-specific silence in thalamocortical circuits precedes hippocampal sharp-wave ripples, Cell Reports (2022). DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111132

Journal information: Cell Reports