Although evidence of our species living in Southeast Asia rainforests dates back at least 70,000 years, the poor preservation of organic material in these areas limits our understanding of their diet and ecological adaptations to these environments. An international team of scientists has now used a new method to investigate the diet of fossil humans: stable zinc isotope analysis from tooth enamel. This method is especially useful for determining whether prehistoric humans and animals primarily ate meat or plants.

Tropical rainforests have long been thought to be a barrier to early Homo sapiens. However, mounting evidence suggests that humans adapted to and lived in Southeast Asia’s tropical rainforest habitats. Some researchers believe that other human species, such as Homo erectus and Homo floresiensis, went extinct in the past because they were unable to adapt to this environment as well as our species. However, we know very little about fossil humans’ ecological adaptations, including what they ate.

The Tam Pà Ling site is particularly important for Southeast Asia palaeoanthropology and archaeology because it contains the oldest and most abundant fossil record of our species in this region

Fabrice Demeter, University of Copenhagen

Zinc isotopes reveal what kind of food was primarily eaten

Researchers examined the zinc stable isotope ratios in animal and human teeth from two locations in Laos’ Huà Pan Province: Tam Pà Ling and the nearby Nam Lot. “The Tam Pà Ling site is particularly important for Southeast Asia palaeoanthropology and archaeology because it contains the oldest and most abundant fossil record of our species in this region,” explains Fabrice Demeter, a researcher at the University of Copenhagen.

However, there is little archaeological evidence in Tam Pà Ling, such as stone tools, hearth features, plant remains, and cut marks on bones. As a result, isotopic approaches are the only way to gain insight into previous dietary reliance.

Nitrogen isotope analysis, in particular, can assist scientists in determining whether past humans consumed animals or plants. However, the collagen in bones and teeth that is required for these analyses is not easily conserved. This problem is exacerbated in tropical areas such as Tam Pà Ling.

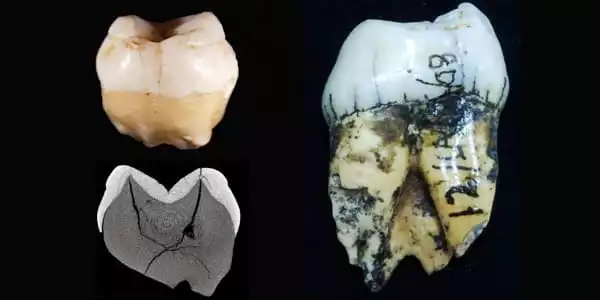

“New methods, such as zinc isotope analysis of enamel,” says study leader Thomas Tütken, professor at Johannes Gutenberg University’s Institute of Geosciences, “can now overcome these limitations and allow us to investigate teeth from regions and periods we could not study before.” “We can now study Tam Pà Ling and learn what kind of food our earliest ancestors in this region ate using zinc stable isotope ratios.”

The first study that reveals the whole diet of fossil humans from Southeast Asia

The fossil human studied in this study dates from the Late Pleistocene, or 46,000 to 63,000 years ago. Water buffaloes, rhinos, wild boars, deer, bears, orangutans, macaques, and leopards were among the mammals studied at both sites. All of these different animals exhibit a variety of eating behaviors, providing an ideal backdrop for determining what humans were eating at the time. The more diverse the animal remains discovered at a given site, the more information researchers can use to better understand the diet of prehistoric humans.

When the zinc isotope values of the Tam Pà Ling fossil Homo sapiens are compared to those of the animals, it strongly suggests that its diet included both plants and animals. This omnivorous diet also differs from the majority of nitrogen isotope data from humans in other parts of the world for the same time period, where a meat-rich diet is almost always discernible.

“Another type of analysis performed in this study – stable carbon isotopes analysis – indicates that the food consumed came solely from forested environments,” says Élise Dufour, researcher at the National Natural History Museum of Paris. “The findings are the oldest direct evidence for Late Pleistocene human subsistence strategies in tropical rainforests.”

Researchers frequently associate our species with open environments such as savannahs or cold steppes. However, this study demonstrates that early Homo sapiens were capable of adapting to a variety of environments. The zinc and carbon isotope results may point to a mix of specialized adaptations to tropical rainforests seen at other Southeast Asian archaeological sites.

“In the future, it will be interesting to compare our zinc isotope data with data from other prehistoric human species of Southeast Asia, such as Homo erectus and Homo floresiensis, to see if we can better understand why they went extinct while our species survived,” says first author Nicolas Bourgon, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.