This block is broken or missing. You might be missing substance, or you could have to empower the first module.

Malignant growth drugs known as designated spot bar inhibitors have demonstrated viability for some disease patients. These medications work by taking the brakes off the body’s lymphocyte reaction, invigorating those insusceptible cells to annihilate cancers.

A few examinations have shown that these medications work better in patients whose growths have an extremely large number of changed proteins, which researchers accept on the grounds that those proteins offer copious targets for lymphocytes to assault. Notwithstanding, for no less than 50% of patients whose cancers show a high mutational weight, designated spot barricade inhibitors don’t work by any stretch of the imagination.

“While extremely effective in the right circumstances, immune checkpoint therapies are not effective for all cancer patients.” This study demonstrates the importance of genetic variation in cancer in influencing therapy efficacy.”

Tyler Jacks, the David H. Koch Professor of Biology and a member of MIT’s Koch Institute for Cancer Research.

Another review from MIT uncovers a potential clarification for why that is. In an investigation of mice, the specialists found that estimating the variety of changes inside a cancer created significantly more exact expectations of whether the therapy would prevail than estimating the general number of transformations.

Assuming that it is approved in clinical preliminaries, this data could assist specialists in better figuring out which patients will benefit from designated spot barricade inhibitors.

“While exceptionally strong in the right settings, safe designated spot treatments are not compelling for all malignant growth patients. This work clarifies the role of hereditary heterogeneity in malignant growth in deciding the adequacy of these medicines,” says Tyler Jacks, the David H. Koch Teacher of Science and an individual from MIT’s Koch Establishment for Disease Exploration.

Jacks; Peter Westcott, a previous MIT postdoc in the Jacks lab who is currently an associate teacher at Cold Spring Harbor Lab; and Isidro Cortes-Ciriano, an exploration bunch pioneer at EMBL’s European Bioinformatics Foundation (EMBL-EBI), are the senior creators of the paper, which shows up today in Nature Hereditary Qualities.

A variety of changes

Across a wide range of diseases, a small number of tumors have what is known as a high tumor mutational weight (TMB), meaning they have an extremely enormous number of transformations in every cell. A subset of these growths has deserts connected with DNA fix, most regularly in a maintenance framework known as DNA crisscross fix.

Since these cancers have such countless altered proteins, they are accepted as great contenders for immunotherapy therapy, as they offer plenty of likely targets for white blood cells to assault. Throughout recent years, the FDA has endorsed a designated spot bar inhibitor called pembrolizumab, which enacts immune system microorganisms by impeding a protein called PD-1, to treat a few sorts of growths that have a high TMB.

Nonetheless, resulting investigations of patients who got this medication found that the greater part of them didn’t answer well or just showed brief reactions, despite the fact that their cancers had a high mutational weight. The MIT group set off to investigate why a few patients answered better compared to other people by planning mouse models that intently imitated the movement of growths with high TMB.

These mouse models convey changes in qualities that drive malignant growth improvement in the colon and lung, as well as a transformation that closes down the DNA jumble fix framework in these cancers as they create. This causes the growth to create numerous extra changes. At the point when the scientists treated these mice with designated spot bar inhibitors, they were amazed to find that not a single one of them responded well to the treatment.

“We checked that we were effectively inactivating the DNA fix pathway, bringing about heaps of changes. The growths very closely resembled those in human diseases; however, they were not more penetrated by lymphocytes, and they were not responding to immunotherapy,” Westcott says.

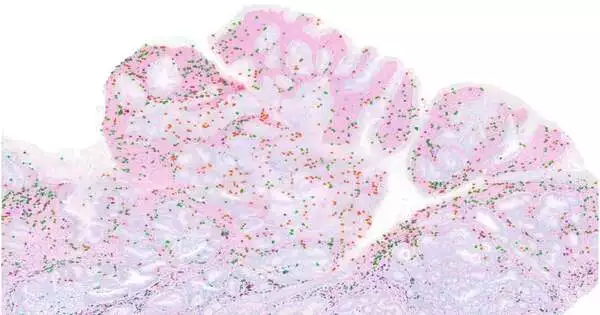

The scientists found that this absence of reaction gives off the impression of being the consequence of a peculiarity known as intratumoral heterogeneity. This actually intends that, while the growths have numerous transformations, every cell in the cancer will, in general, have unexpected changes in comparison to a large portion of different cells. Thus, every individual malignant growth change is “subclonal,” implying that it is communicated in a minority of cells. (A “clonal” transformation is one that is communicated in the cells in general.)

In additional examinations, the scientists investigated what occurred as they changed the heterogeneity of lung cancers in mice. They found that in growths with clonal transformations, designated spot bar inhibitors were exceptionally viable. Notwithstanding, as they expanded the heterogeneity by blending cancer cells with various transformations, they found that the therapy turned out to be less successful.

“That shows us that intratumoral heterogeneity is truly bewildering the resistant reaction, and you truly possibly get areas of strength for the designated spot bar reactions when you have a clonal growth,” Westcott says.

Inability to enact

Apparently, this powerless lymphocyte reaction happens on the grounds that the immune system microorganisms basically see enough of no specific carcinogenic protein, or antigen, to become enacted, the specialists say. At the point when the specialists embedded mice with cancers that contained subclonal levels of proteins that ordinarily incite areas of strength for a reaction, the immune system microorganisms neglected to turn out to be sufficiently strong to go after the growth.

“You can have these intensely immunogenic growth cells that, in any case, ought to prompt a significant lymphocyte reaction; however, at this low clonal level, they totally go into secrecy, and the safe framework neglects to remember them,” Westcott says. “There’s insufficient antigen that the lymphocytes perceive, so they’re inadequately prepared and don’t obtain the capacity to kill growth cells.”

To check whether these discoveries could reach out to human patients, the scientists broke down information from two little clinical preliminary studies of individuals who had been treated with designated spot bar inhibitors for either colorectal or stomach malignant growth. In the wake of examining the arrangements of the patients’ cancers, they found that patients’ whose growths were more homogeneous responded better to the therapy.

“How we might interpret malignant growth is something we work on constantly, and this translates into better persistent results,” Cortes-Ciriano says. “Endurance rates following a disease finding have essentially been worked on in the past 20 years because of cutting-edge research and clinical examinations. We realize that every patient’s disease is unique and will require a custom-made approach. Customized medication should consider a new examination that is assisting us with understanding the reason why disease medicines work for certain patients, but not all.”

The discoveries likewise propose that treating patients with drugs that block the DNA fix pathway in order to create more changes that white blood cells could target may not help and could be destructive, the scientists say. One such medication is currently in clinical preliminaries.

“Assuming you attempt to change a current malignant growth, where you as of now have numerous disease cells at the essential site and others that might have spread all through the body, you will make a very heterogeneous assortment of malignant growth genomes. Moreover, what we showed is that with this high intratumoral heterogeneity, the white blood cell reaction is confounded, and there is definitely no reaction to insusceptible designated spot treatment,” Westcott says.

More information: Peter M. K. Westcott et al, Mismatch repair deficiency is not sufficient to elicit tumor immunogenicity, Nature Genetics (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41588-023-01499-4