Movement catch innovation has applications in a large number of fields, including diversion, medication, and sports, to give some examples. However, imagine a scenario where the estimations these frameworks depended on were established in friendly practices and one-sided suspicions, prompting blunders that become imbued over the long run.

This question is at the core of a new exploration co-created by Mona Sloane, an associate teacher of information science and media learning at the College of Virginia. The work is distributed on the arXiv preprint server.

Sloane and her co-creators—Abigal Jacobs, an associate teacher of data at the College of Michigan; Emanuel Greenery, an examination researcher at Intel Labs; Emma Harvey, a doctoral understudy at Cornell’s School of Data Science; and Hauke Sandhaus, a doctoral understudy at Cornell Tech—utilize social practice hypothesis as a focal point to look at how certain presumptions have become implanted in the plan and development of movement catch innovation as the decades progressed.

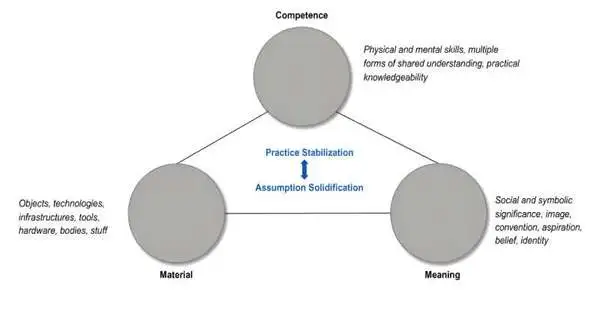

The social practice hypothesis, which the paper makes sense of, takes a gander at ways of behaving that should be visible across networks all through various timeframes, as opposed to zeroing in barely on an item or individual as a unit of request. This approach permits scientists to uncover the suppositions that are incorporated into innovative frameworks, which can, possibly, uncover the damages these frameworks could cause.

Sloane and her teammates led an orderly writing survey of 278 papers relating to movement catch research. They partition this writing into three parts: establishment, 1930–79; normalization, 1980–99; and advancement, 2000–present.

Inside those three times, the creators distinguish six kinds of blunders—which, they contend, give basic bits of knowledge into movement catch rehearses across the different time spans.

For instance, in the main time—where works zeroed in on estimating the human body, which helped establish the groundwork for movement with catching innovation—the examination referred to one review that meant to recognize the best plan of a cockpit. To do as such, the review’s creator utilized the body portion boundaries of eight more seasoned, white male corpses, and the subsequent estimations before long arose as the acknowledged benchmarks utilized by the U.S. Flying Corps.

Mistakes in the estimation of the human body, or anthropometric blunders, were normal in the establishment period, the creators find. At the latest, mistakes relating to the calculations used to break down information are common.

Classifying and grasping the ramifications of these blunders and the presumptions they depend on could significantly affect innovation and society. For example, vehicle security measures that were carried out in light of life-sized models intended to look like a normal male body have brought about higher injury rates for females. This is only one illustration of deficient subgroup legitimacy testing prompting destructive results that the paper features.

Through their examination, Sloane and her co-creators devise a layout for future exploration on friendly practice in the plan and utilization of advances and furthermore enlighten the unfortunate establishments on which current movement catch frameworks have, on occasion, been fabricated. Their discoveries highlight the numerous ways in which suspicions have been conveyed across various authentic periods, turning out to be important for the foundation of a few current mechanical frameworks.

More information: Emma Harvey et al, The Cadaver in the Machine: The Social Practices of Measurement and Validation in Motion Capture Technology, arXiv (2024). arxiv.org/abs/2401.10877v1