Nazca boobies can live to 28 years old, yet in their late adolescents, their capacity to raise chicks declines significantly. David Anderson, a professor of biology at Wake Forest University, has wondered for a long time why their breeding declines with age. However, by examining their capacity to forage, or search for and capture food, a new study that was recently published in Ecology and Evolution may assist in answering the question.

The research team, led by Anderson, wanted to find out how the foraging behavior of Nazca boobies changes with age and environmental conditions, which may affect how well these birds can raise their young.

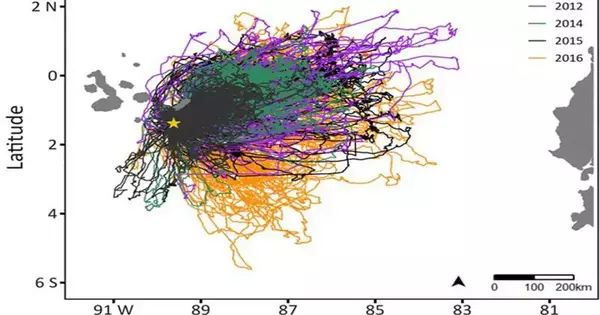

The lead creator of the review, and afterward Wake Woodland graduate understudy Jenny McKee, joined little GPS lumberjacks to in excess of 800 birds to follow their developments adrift. The researchers removed the loggers and downloaded the GPS data when the birds returned to the nest after a foraging trip, which could sometimes last a week, to see where the birds went in search of food.

According to McKee, “I found it fascinating that we could use these small GPS loggers to spy on their activity.” Each time we connected the GPS to the computer, downloaded the data, and observed their tracks, it was like Christmas morning. It gave a glimpse of the things the birds saw when they were away from the nest.

“I found it fascinating that we could spy on their activities using these small GPS loggers. Every time we connected the GPS to the computer, downloaded the data, and watched their tracks, it felt like Christmas morning. It gave a glimpse into what the birds were up to when they were not in the nest.”

Jenny McKee, Lead author of the study, and then Wake Forest graduate student,

The research by Anderson, who studies a variety of seabird species, including the waved albatross, blue-footed boobies, and Nazca boobies, spans decades. On Isla Espaola, a Galápagos island of 37 square miles, he and his team have been banding Nazca boobies for nearly 40 years.

The boobies’ ability to forage was affected by the environment, particularly the Pacific Ocean’s sea surface temperature. Boobies traveled shorter distances and spent less time foraging and searching for food when the water was warm, like during the 2015–16 El Nio, suggesting that food was easier to find.

McKee stated, “This was surprising because we frequently think that El Nio is really bad for seabirds.” However, Emily Tompkins, a co-author, found that boobies had larger clutches in El Nio-like conditions but that chick survival was lower later in the 7-8 month breeding season. This finding is consistent with previous research.

The specialists likewise tracked down decreases in rummaging with advanced age, especially for female boobies. The team found that the oldest females traveled 140 miles farther and spent 15 more hours foraging than the middle-aged birds when they compared 12-year-old females to 24-year-old females, the oldest birds in the study.

According to these findings, the inefficient foraging efforts of elderly females may have contributed to their inability to reproduce. The eggs or chicks may become prey for Galápagos mockingbirds or hawks if older females spend more time foraging, forcing their mate to leave the nest to eat.

However, the decades-long data collected from Nazca boobies continues to reveal fascinating details about aging—a difficult task for a wild animal. Booby aging may be better understood with the help of GPS data on their foraging or dive depth measurements during the breeding season.

More information: Jennifer L. McKee et al, Age effects on Nazca booby foraging performance are largely constant across variation in the marine environment: Results from a 5‐year study in Galápagos, Ecology and Evolution (2023). DOI: 10.1002/ece3.10138