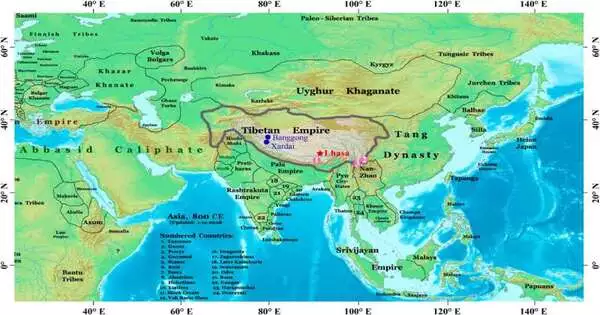

The Tibetan Realm was the world’s most noteworthy rise domain, sitting over 4,000m above ocean level, and flourished from 618 to 877 CE. Home to an expected 10 million individuals, it spreads over roughly 4.6 million km2 across East and Focal Asia, reaching out into northern India.

Taking into account the antagonistic circumstances for populations to grow, including hypoxia, where oxygen concentrations are 40% lower than the adrift level, it is fantastic that the domain prospered. In any case, its breakdown in the ninth century isn’t completely perceived, and new exploration distributed in Quaternary Science Surveys planning to unravel the job environment might have played toward the finish of an extraordinary civilization.

Zhitong Chen, from the Establishment of Tibetan Level Exploration, China, and associates went to the geographical record of lake residue (paleolimnology) to decide how the climate changed 12 centuries prior. Xardai Co.’s freshwater lake silt protects the remaining parts of infinitesimal single-celled green growth known as diatoms, with the examination group noticing a massive change from planktonic assortments (those floating inside a water body, by and large closer to the surface) to benthic structures (living close to the lake floor). This is deciphered as addressing a shift to drier circumstances, thus bringing down lake levels.

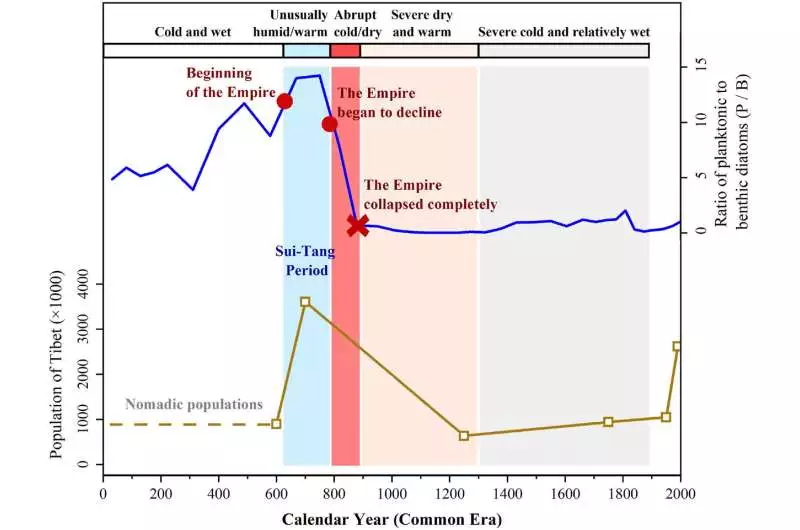

There is an unmistakable example of high lake levels, recommending warm and moist circumstances during the ascent and pinnacle of the Tibetan Domain ca. 600–800 CE, before conditions escalated to a serious dry season, agreeing with the domain’s breakdown ca. 800-877 CE. Chen and his teammates connect the dry season with the probability of yield disappointment, prompting social agitation among the populace, followed by strict and political difficulties, subsequently leading to the domain’s death.

The Tibetan Level is very sensitive to changes in the environment because of its rise, with temperature and precipitation vacillations fluctuating altogether from the normal experience across the Earth. The review lake, Xardai Co., is regularly ice-covered today from November to April; however, it encounters neighborhood temperature shifts between -12.1 °C and 14.1°C, as well as 71 mm of yearly precipitation. These variables have significant outcomes for lake levels and, hence, the creatures that live inside them.

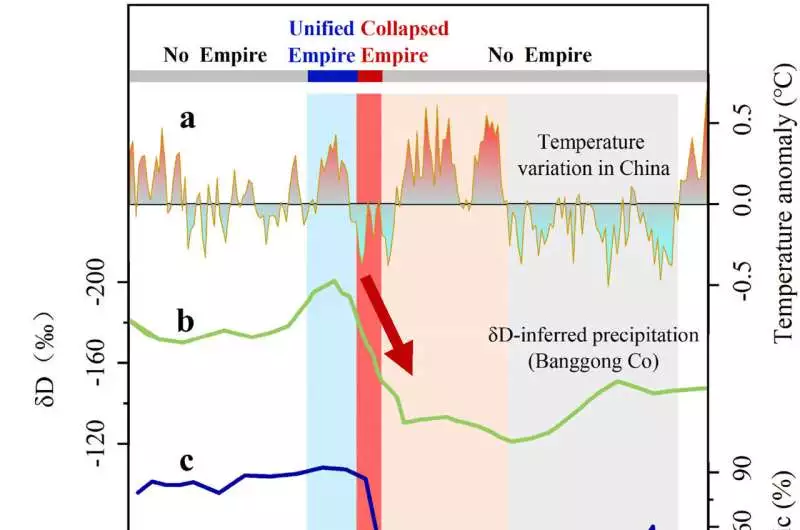

Temperature and precipitation records from the Tibetan Level coordinated with the proportion of planktonic to benthic diatoms as a sign of lake level changes. Tops in all information happen in the time of the flourishing Tibetan Realm in warm and damp circumstances, before sensational changes mean the megadrought corresponding with domain breakdown. Following this was the warm-dry season of the Archaic Warm Period and, afterward, the relatively wet Little Ice Age. Credit: Chen et al., 2023.

Inside the center bore from the lake in 2020, 160 diatom taxa were recognized, but only 23 were viewed as essentially bountiful.

Before ca. 800 CE, the diatom collections were overwhelmed by two planktonic structures, Lindavia radiosa and Lindavia ocellata, and more modest overflows of Amphora pediculus and Amphora inariensis. Here, the proportion of planktonic to benthic structures crested in the wet and moist circumstances that raised lake levels.

The tipping point at 800 CE anyway sees a quick expansion in benthic diatoms Amphora pediculus and Amphora inariensis, while the previously mentioned untamed water Lindavia radiosa and Lindavia ocellata declined. Yet again, this diatom local area persevered until 1300 CE, when lake levels started to ascend during the Little Ice Age.

The information was matched against other paleoenvironmental pointers from across the Tibetan Plateau and affirmed that these environmental changes were steady across the area and not exclusively limited to the review lake. This included precipitation records deduced from a subsequent lake found 50km north of Xardai Co., Banggong Co., as well as temperature records from China.

Connecting the environment’s changes to its effect upon the number of inhabitants at the time, horticulture and domesticated animal cultivation were the predominant jobs, with crop creation in the Yarlung Zangbo Stream valley and brushing on the Qangtang Level. During domain development, the glow and rain would have supported crop creation and wild fields for nibbling creatures, as well as raised the height at which they could be developed. Ponies, goats, and yaks are brushing creatures and were significant for the exchange economy of Tibet.

Tibet’s populace throughout recent years coordinated with Xardai Co. lake records of the planktonic to benthic diatom proportion, demonstrating lake levels and subsequently environmental change. Credit: Chen et al., 2023.

In any case, the similarly unexpected environmental decline over 60–70 years would have hindered plant development, prompting a decrease in horticulture and peaceful brushing. This would fundamentally affect the endurance of the populace with food deficiencies as well as the monetary thriving of an exchange-dependent realm. Social agitation probably followed, with the fracture of various political plans at last prompting the end of the Tibetan Realm.

Today, farming and peaceful exercises represent over a portion of Tibet’s yearly pay, so understanding the environment’s cost for networks in brutal conditions is central to guaranteeing they get by, however flourishing.

More information: Zhitong Chen et al, Collapse of the Tibetan Empire attributed to climatic shifts: Paleolimnological evidence from the western Tibetan Plateau, Quaternary Science Reviews (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2023.108280