Indeed, even worms have a ticking richness clock. More seasoned worms are less effective at fixing broken DNA strands while making egg cells, a piece of a cycle that is fundamental for richness. Another review from College of Oregon (UO) scholars proposes one potential explanation: generational change eases back with age.

Scientists from the lab of Diana Libuda report the discoveries in a paper distributed Nov. 7 in PLOS Hereditary Qualities.

Every sperm or egg cell has only a fraction of the chromosomes found in a normal cell.During meiosis, the cell division process that structures sperm and eggs, the parent cells should equally isolate their DNA. The costs of a mistake can be high, because incorrectly isolated chromosomes are a major cause of birth defects.

To take care of business, cells utilize an amazing system: they purposely break their strands of DNA and then fix them.

“It’s one of biology’s most astounding processes. The repair process physically joins the chromosomes and serves as an organizing point to guarantee that the chromosomes are distributed equally.”

Erik Toraason, a former graduate student in Libuda’s lab who led the work.

“It’s perhaps the most astounding cycle in science,” said Erik Toraason, a previous alumni understudy in Libuda’s lab who drove the work. The maintenance cycle “truly locks the chromosomes together and gives an association point” that guarantees that the chromosomes are isolated equally.

Toraason needed to comprehend how maturing influences those cycles. “The explanation for why these cells are so helpless to maturing isn’t certainly known,” said Toraason, a postdoctoral scientist at Princeton University.”However, one of the elements regarded as significant is genome repair and the possibility that it may decline, rendering oocytes—creating eggs—helpless against deserts.”

Worms ended up being an optimal proving ground for those inquiries. C. elegans worms are normally bisexual, meaning each worm produces two eggs and sperm. Yet, because of a hereditary change that nixes sperm creation, scientists can make egg-delivering worms that are practically female.

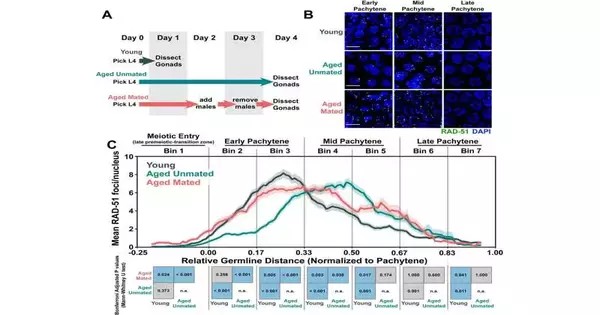

Toraason and her research partner Vikki Adler utilized that stunt to isolate the impacts of maturing from the impacts of running out of sperm, which happens regularly as bisexual worms age and furthermore prompts a decrease in ripeness.

Running out of sperm appeared to influence the rate at which the bisexual worms made breaks in their egg cell DNA, the analysts found. Yet, the capacity to fix DNA breaks declined with age even in the female worms, free of sperm levels.

“We found that framing breaks are changed when you run out of sperm, but break fix is impacted by the maturing system rather than sperm,” Libuda said.

The group doesn’t yet have any idea why this cycle changes with age, but, basically, for worms, it very well may be connected with a change in assets. In worms that have spent all their sperm, unfertilized oocytes at times become a food hotspot for posterity. Since the oocytes aren’t being utilized for generation, the worms never again need to spend assets breaking and fixing their DNA.

More information: Erik Toraason et al, Aging and sperm signals alter DNA break formation and repair in the C. elegans germline, PLOS Genetics (2022). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1010282

Journal information: PLoS Genetics