According to a new study, extreme heat currently impacts over two billion urban inhabitants worldwide.

The new study is the first to look in depth at global trends in high heat exposure across metropolitan locations. For nearly three and a half decades, the survey covered over 13,000 communities.

Scientists discovered that exposure to harmful temperatures has grown by 200 percent since the mid-1980s, with poor and marginalized people being the most vulnerable.

Our work shows that exposure to high heat in metropolitan places is far more widespread—and increasing in many more areas—than we previously thought, says coauthor Kelly Caylor, director of the Earth Research Institute at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Over the last 30 years, nearly one in every five people on the planet has experienced an increase in exposure to metropolitan heat.

The study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences is simply the first of many that will investigate the growing threat of extreme heat and its consequences for society and the environment.

Cascade Tuholske, the study’s lead author, was first interested in how climate change would affect urban food security, particularly among low-income households.

Many of these people are not necessarily food insecure in terms of, say, a calorie deficit,” he continues, “but they spend a large portion of their income on food.” This puts them at risk, especially since excessive heat frequently affects labor output and, thus, income and food security.

As a result, understanding urban food security necessitates determining how many people are affected by excessive heat.

“I went through the literature and discovered that we didn’t have a baseline understanding of where excessive heat impacts humans in cities at tiny scales,” says Tuholske, who is now a postdoctoral research scientist at Columbia University’s Earth Institute.

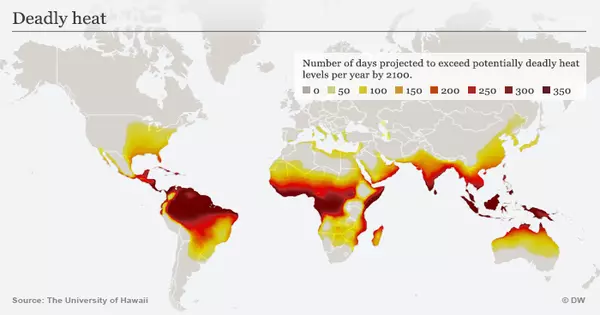

Extreme heat is being experienced all around the planet.

While piecing together this baseline, the authors found two major obstacles. The first step was to collect relatively reliable population figures. Tuholske explains that researchers don’t exactly know how many people exist on Earth because there are numerous regions where population estimates are impossible owing to terrain, infrastructure, or governance.

Tuholske obtained his population data from the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre’s global human settlement database (JRC). The commission assesses the distribution of urban inhabitants by combining the most recent census data with Landsat remote imaging techniques.

The second key problem was gathering meteorological data to characterize heat exposure globally. Fortunately, the Climate Hazards Center at UC Santa Barbara just produced a new dataset with this information: the Climate Hazards Infrared Temperature with Stations (CHIRTS).

“Our study reveals that exposure to extreme heat in urban areas is much more widespread—and increasing in many more areas—than we had previously realized. Almost one in five people on Earth experienced increases in exposure to urban heat over the past 30 years.”

says coauthor Kelly Caylor, director of the Earth Research Institute at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

“CHIRTS is the temperature equivalent of our widely used CHIRPS precipitation product,” explains cofounder and Climate Hazards Center director Chris Funk. “It, like CHIRPS, blends very high-resolution long-term average maps with time-varying satellite and station observations.” The dataset offered the exact information that the authors needed for this paper.

Heat maps throughout the world

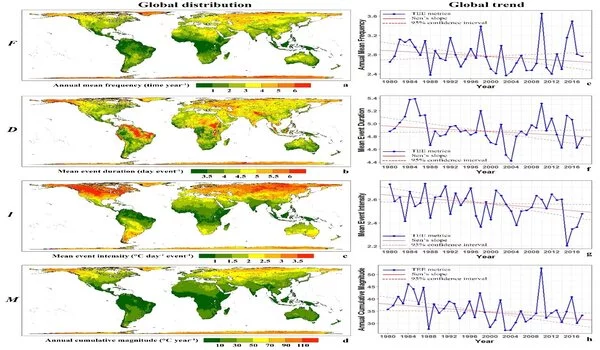

To assess excessive heat, the researchers utilized a parameter known as the wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT) throughout their study. A WBGTindex is an index that takes temperature, humidity, wind speed, and radiant heat into account. It was created to better properly depict how ambient conditions affect the human body, similar to a “feels like” rating.

Tuholske used a grid to divide the Earth’s surface into this. He calculated the highest temperature and relative humidity for each cell using his models and records from 1983 to 2016. This allowed him to compute the WBGT.

Tuholske then superimposed this grid on a population map of cities. He chose a wet bulb globe temperature of 30 °C (86 °F) as the extreme heat exposure threshold. The International Standards Organization considers this number to pose a high risk of occupational heat-related illness, hence it is often utilized.

For each year, he counted the number of days each cell was above the WBGT of 30°C and multiplied that number by the population in that cell. The number of person-days per year of high heat exposure was calculated at a resolution of 0.05° latitude by 0.05° longitude.

“We discovered that urban high heat exposure climbed 200 percent globally in 34 years,” Tuholske said. The researchers were also able to differentiate between the effects of population growth and rising temperatures. They discovered that population growth accounted for two-thirds of the year-to-year rise, with warming accounting for the remaining one-third.

There are few choices for escaping the heat.

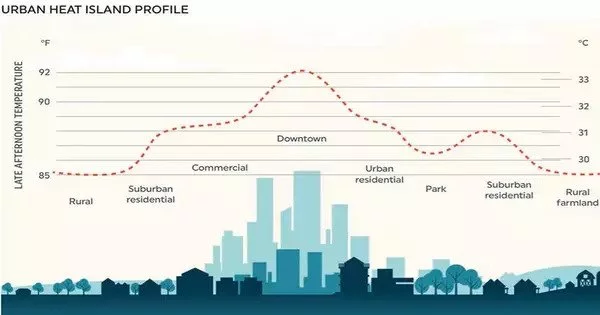

In an upcoming work, they intend to further extract the independent inputs from climate change and the urban heat island effect.

“This study underscores that excessive heat exposure is already increasing in almost half of all cities and towns around the world,” Funk says. Also, population growth is a major contributor to increased risk. We must consider these demographic factors, as well as climate change.

According to the authors, economically disadvantaged and marginalized people are particularly vulnerable to excessive heat exposure. Caylor argues that, in addition to the risk of food hardship, these people have fewer alternatives for mitigating their exposure to high heat. They also tend to live in cities, which are prone to more severe and extended periods of excessive heat.

Indeed, the hazard of excessive heat varies at the regional and even city levels, which the authors intend to investigate further in the future. Only 25 metropolitan locations accounted for over a fifth of the global change in high heat exposure. Dhaka, Bangladesh, Delhi, India, Kolkata, India, and Bangkok, Thailand ranked first through fourth.

6,000 towns

This isn’t just a problem in big cities. According to the authors, there was a considerable increase in the amount of high heat exposure in nearly 6,000 localities.

And the influence of heat on a population varies greatly, affecting locations other than those addressed in this study. For example, the Pacific Northwest’s summer heat wave in 2021 proved harmful since the region wasn’t prepared to deal with high temperatures.

“There isn’t a lot of air conditioning in Seattle or Portland,” explains Tuholske. So, while the conditions were not as extreme as in Delhi or Dubai, the impact was still significant.

Tuholske explains that the authors are unable to apply the findings of this study to specific city outcomes. Nonetheless, the report and the information on which it is based create the groundwork for a slew of future research.

While Tuholske chose to focus on urban heat exposure for this study, the abundance of data available will allow academics to analyze a wide range of issues, trends, and repercussions.

The Climate Hazards Center intends to begin releasing operational updates for the CHIRTS dataset by the end of 2021. The update will also contain climate change forecasts for 2030 and 2050.

Funk hopes to eventually develop a combined observation and forecast system that can be integrated into a heat wave early warning system.

Both the University of California, Santa Barbara’s Climate Hazards Center and Columbia University’s Earth Institute contribute to early warning systems for extreme weather events, putting the authors in a good position to make this happen. The Climate Hazards Center already has a system in place for droughts, but it is seeking to enhance its capacity to predict extreme heat and precipitation.

Futurity was the first to publish this article.