Scientists at the College of Massachusetts Amherst as of late distributed a couple of papers that, together, give the most point-by-point guides to date on how 144 normal obtrusive plant species will respond to 2°C of environmental change in the eastern U.S., as well as the role that nursery habitats as of now play in cultivating future intrusions.

Together, the papers, distributed in Variety, Circulations, and BioScience, and the openly accessible guides, which track species at the region level, vow to give obtrusive species chiefs in the U.S. the apparatuses they need to proactively coordinate their administration endeavors and adjust now for the upcoming hotter environment.

Planning for future overflow

One of the significant obstacles to tending to the danger of obtrusive species is deciding when and where an animal group goes too far from being non-local to obtrusive. A solitary event of, say, purple loosestrife doesn’t make an intrusion. Obtrusive plant chiefs need to know where an animal group is probably going to dominate, outcompeting local plants and changing the environment.

“Because managers have few resources to control invasions, we don’t want to waste time focusing on species that are unlikely to become invasive in a given area. But determining what will become invasive and where has proven to be surprisingly difficult.”

Bethany Bradley, professor of environmental conservation at UMass Amherst and the senior author of both papers,

Or on the other hand, as Bethany Bradley, teacher of natural preservation at UMass Amherst and the senior creator of the two papers, puts it, “Supervisors have not very many assets to control attacks, so we would rather not sit around zeroing in on species far-fetched to become obtrusive in a given region. Be that as it may, the subject of what will become obtrusive and where has been shockingly interesting to reply.”

“In the event that we can proactively distinguish these species and the locales they are probably going to become plentiful in as the environment warms, then, at that point, we can head off a significant natural danger before it’s past the point of no return,” adds Annette Evans, a postdoctoral individual at UMass Amherst’s Upper East Environment Variation Science Center and lead creator of the paper on overflow and future obtrusive areas of interest.

To do as such, the group sifted through 14 current obtrusive species data sets accumulated by many normal asset administrators to initially pinpoint which species are right now plentiful and where, geologically, those overflow hotpots happen.

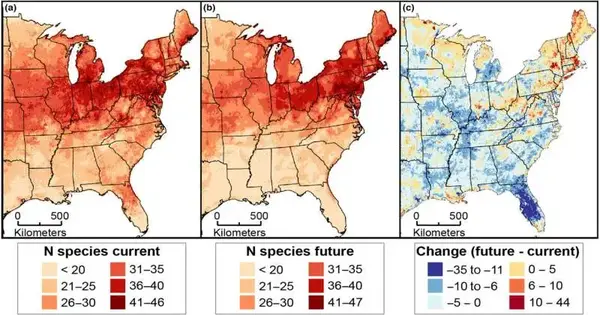

They zeroed in on the eastern U.S. (east of the 100th meridian, which runs from the center of North Dakota through the focal point of Texas—a subsequent paper will zero in on the western U.S.) and found that the most sizzling areas of interest are around the Incomparable Lakes, the mid-Atlantic, and along the northeastern shores of Florida and Georgia. Every one of these areas has the right blend of conditions to support bountiful populations of in excess of 30 unique obtrusive plants at present.

They then, at that point, ran their information on 144 plants through a progression of models that anticipated where the areas of interest would happen under 2°C of warming.

What they found is that the vast majority of the species will move their reaches toward the upper east by a normal of 213 kilometers, a pattern likewise reflected in movements to overflow areas of interest. In certain states, warming temperatures will make at present unacceptable regions favorable for bountiful pervasions of up to 21 new plant species, and the reach moving could worsen the impacts of up to 40 as-of-now plentiful invasives. Then again, 62% of presently plentiful obtrusive species will see a lessening in living space for enormous populations in the eastern U.S.

Be that as it may, insights aren’t sufficient. “We’ve made something considerably easier to use,” says Evans: a progression of freely accessible reach maps for individual species, which can assist with establishing chief emergencies that most need their consideration, as well as state-explicit watch records.

How plant nurseries could attack seeds

“At the point when individuals consider how obtrusive plant species spread, they could expect species to be moving as a result of birds or the breeze scattering seeds,” says Evelyn M. Beaury, lead creator of the paper on cultivation and intrusive species, as well as a postdoctoral scientist at Princeton who finished this examination as an expansion of what her alumni learned at UMass Amherst. “Yet, business nurseries that sell many different invasives are really the essential pathway of intrusive plant presentation.”

However, analysts have long known that invasive species are connected to the cultivation exchange. Beaury and her co-creators, including Evans and Bradley, thought about how frequently invasive species are sold in similar regions where they are plentiful. What’s more, how should nurseries be compounding the issue of environment-driven intrusion?

It just so happens that the response to the two inquiries is great.

Utilizing a contextual investigation of 672 nurseries around the U.S. that sell a total of 89 intrusive plant species and afterward running the outcomes through the very models that the group used to foresee future areas of interest, Beaury and her co-creators observed that nurseries are right now planting the seeds of attack for over 80% of the species examined. Assuming left unrestrained, the business could work with the spread of 25 species into regions that become appropriate with 2°C of warming.

Besides, 55% of the intrusive species were sold within 21 kilometers (13 miles) of a noticed attack—the middle distance individuals across the U.S. go to purchase finishing plants. At the end of the day, regular groundskeepers who purchase plants at their neighborhood nurseries could accidentally assist with propagating intrusion and related environmental damage on their strict terraces.

“In any case, there’s uplifting news here,” says Beaury. “This is whenever we first have genuine numbers to show the association between plant nursery deals and the spread of obtrusive species—including intrusions that happen down the road from nurseries as well as across state borders. Since we have the information, we have a staggering open door to be proactive, to work with the business, buyers, and plant supervisors to ponder what our nurseries mean for U.S. biological systems.”

The group has likewise assembled an openly accessible rundown of 24 normally sold obtrusive plants with an expanded hazard of spreading through environmental change in the upper east, from butterfly shrubbery to English ivy, to be kept away from, and local other options, like bottlebrush buckeye and wild blue phlox.

“These two papers together make plainly clear that, besides the fact that we are working with current attacks through the decorative plant exchange, we are likewise working with future environment-driven attacks,” says Bradley. “Yet with these papers, guides, and watchlists, we can pinpoint which species are most troubling where, both now and in the next few decades. These are significant new apparatuses in obtrusive plant chiefs’ tool kits.”

More information: Annette E. Evans et al, Shifting hotspots: climate change projected to drive contractions and expansions of invasive plant abundance habitats, Diversity and Distributions (2023). DOI: 10.1111/ddi.13787

Evelyn M Beaury et al, Horticulture could facilitate invasive plant range infilling and range expansion with climate change, BioScience (2023). DOI: 10.1093/biosci/biad069