An exploration group has fostered a better approach to testing patients for Coronavirus by examining the body’s resistant reaction at a subatomic level. Their method could detect diseases with close and wonderful precision just hours after openness—far earlier than ebb and flow Coronavirus tests can. The group depicts its advancement, which is still in the beginning phases of improvement, in the February 27 issue of Cell Reports Strategies.

Most existing Coronavirus tests “rely on a similar rule,” which is that you have a noticeable amount of viral material, for example, in your nose,” says focus on lead creator Honest Zhang, who worked on the task as a Flatiron research individual at the Flatiron Foundation’s Center for Computational Science (CCB) in New York City.” That represents a test when you’re in the contamination time window from the start and you haven’t gathered a ton of viral material or you’re asymptomatic.”

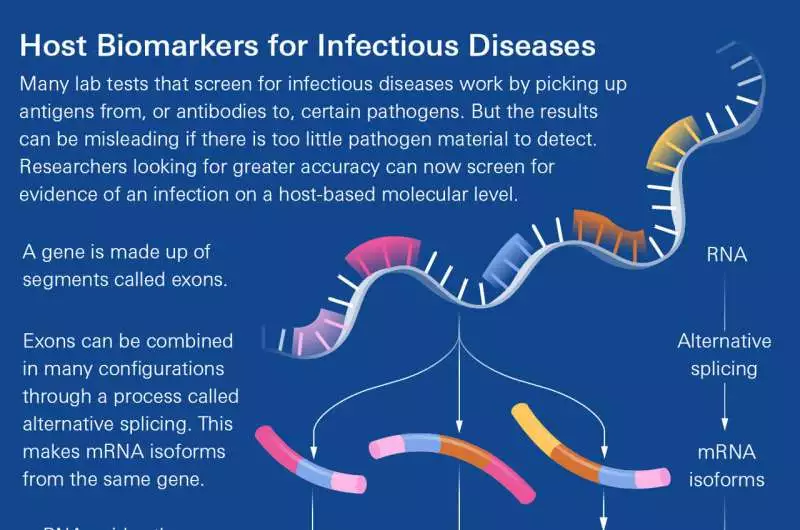

The new procedure is rather founded on how our bodies mount a resistant reaction when attacked by SARS-CoV-2, the infection that causes coronavirus. When the attack begins, explicit qualities become active. Fragments of those qualities produce mRNA particles that guide the structure of proteins. The specific mix of those mRNA particles changes the kinds of proteins created, incorporating proteins with infection-battling capabilities. The new technique can with certainty distinguish when the body is mounting a safe reaction to the coronavirus infection by estimating the overall overflow of the different mRNA atoms. The new review is quick to utilize such a way to deal with and analyze an irresistible sickness.

“It was absolutely astonishing how nicely it worked. It’s a viable alternative and complement to traditional PCR tests.”

Zhang, now an assistant professor at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

The experts fine-tuned their method by using blood tests from a 2020 study of US Marine volunteers who were infected with Coronavirus. The analysts’ computational system distinguished in excess of 1,000 sickness-related mRNA-variation proportion changes.

An infographic makes sense of another technique for diagnosing patients with coronavirus. Credit: Lucy Perusing Ikkanda/Simons Establishment

When scrutinized using genuine blood tests, the new strategy yielded a great 98.4 percent precision rating. That is particularly great as the methodology works similarly on asymptomatic patients, for whom quick antigen tests can be under 60% precise.

“It was truly astonishing that it functioned admirably,” says Zhang, presently an associate teacher at Cedars-Sinai Clinical Center in Los Angeles. “It’s a promising alternative option and an integral way to deal with traditional PCR tests.”

The new methodology isn’t ready to go yet, Zhang says. He and his partners just tried blood tests instead of the nasal examples that are more normal and advantageous for diagnosing coronavirus. Additionally, they need to ensure they can recognize the body’s response to the coronavirus and its reaction to contamination brought about by other infections, like colds.

The scientists are optimistic, however, because other research groups have made significant progress on tests that examine which qualities turn on. Those equivalent tests could, without much of a stretch, be added to the mRNA examination created in the new review, subsequently delivering surprisingly better outcomes, Zhang says. “Anything they can do, we can most likely investigate and unite on,” including getting cases not long after beginning openness.

Zhang worked on the project’s computational aspects alongside CCB researcher Natalie Sauerwald and CCB representative and chief for genomics Olga Troyanskaya. Stuart Sealfon of the Icahn Institute of Medication at Mount Sinai in New York City drove the work on the review’s natural parts, with Standard BioTools in San Francisco fostering the testing arrangement.

More information: Zijun Zhang et al, Blood RNA alternative splicing events as diagnostic biomarkers for infectious disease, Cell Reports Methods (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.crmeth.2023.100395