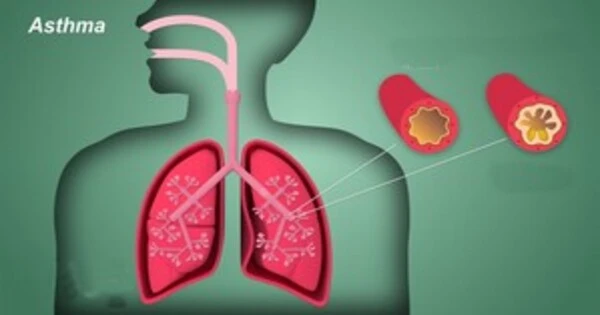

A world-first study found that having a food allergy as a baby is connected to asthma and impaired lung function later in childhood. The study, coordinated by Murdoch Children’s Research Institute and published in the Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, discovered that early-life food allergy was linked to an increased risk of asthma and impaired lung expansion at six years of age.

According to Murdoch Children’s Associate Professor Rachel Peters, this is the first study to look at the link between challenge-confirmed food allergies in infancy and asthma, as well as poorer lung health later in childhood.

The Melbourne study included 5276 infants from the HealthNuts project who were subjected to skin prick testing for common food allergens such as peanut and egg, as well as oral meal challenges to determine food allergy. At six years old, the children underwent additional food allergy and lung function tests.

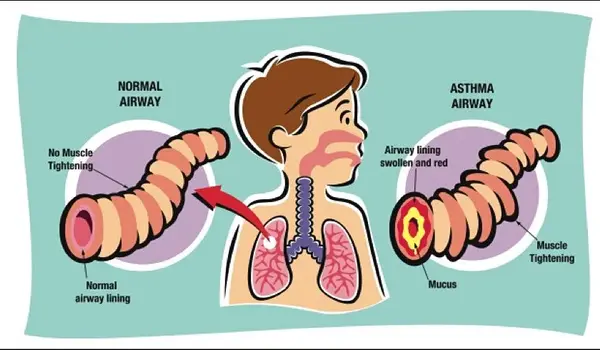

According to the study, 13.7% of children by the age of six had been diagnosed with asthma. Babies with food allergies were nearly four times more likely to develop asthma by the age of six, compared to children who did not have food allergies. The impact was greatest in children whose food allergy remained until age six, as opposed to those who had outgrown it. Children with food allergies were also more likely to have decreased lung function.

The growth of infants with food allergy should be monitored. We encourage children who are avoiding foods because of their allergy to be under the care of a dietician so that nutrition can be catered for to ensure healthy growth.

Associate Professor Rachel Peters

Associate Professor Peters stated that food allergy in infancy, whether resolved or not, was associated with poorer respiratory outcomes in children. “This association is concerning given reduced lung growth in childhood is associated with health problems in adulthood including respiratory and heart conditions,” she went on to say.

“Lung development is linked to a child’s height and weight, and children with food allergies may be shorter and lighter than their counterparts without allergies. This could explain the relationship between food allergies and lung function. Both food allergies and asthma develop from similar immunological reactions.”

“The growth of infants with food allergy should be monitored. We encourage children who are avoiding foods because of their allergy to be under the care of a dietician so that nutrition can be catered for to ensure healthy growth.”

Food allergy affects 10 per cent of babies and 5 per cent of children and adolescents. Suba Slater’s, son Zane, 15, is allergic to eggs, sesame and peanuts and has asthma.

“As a newborn he developed eczema on his back and I thought because I was breastfeeding, there was something in my diet causing the rash,” she went on to say. “We took him into hospital for tests, which confirmed the multiple food allergies.”

Suba stated that she was not well versed about the link between food allergies and asthma before to Zane’s diagnosis.

“We were much focused and vigilant around the food allergy aspect given our eldest child also has allergies,” said the mother. It is critical to demonstrate this link through study and raise awareness among parents and medical professionals. When we found Zane had food allergies, we had no idea to look out for asthma, and it was not on our radar.

“Looking back, he most likely had asthma long before we could hear that he was struggling with his breathing. If we had been aware of the association we would have sought medical help much sooner.”

Suba said Zane had participated in several food challenges at the Murdoch Children’s but his asthma had complicated his participation at times. “By taking part in the food challenges we have found out that Zane is now able to tolerate egg in baked goods and certain nuts much more and has learnt how to include these foods in his diet,” she said.

“But before he does a challenge he is required to take a spirometry test to make sure his lung function is at its best in case the allergenic food triggers his asthma. There are times where he has missed appointments because his lungs haven’t been strong enough.”

Professor Shyamali Dharmage of Murdoch Children’s and the University of Melbourne said the findings would assist clinicians adapt patient care and encourage more vigilance when monitoring respiratory health. Children with food allergies should be seen by a clinical immunology or allergy specialist for continuous care and education.

Professor Dharmage advised doctors and parents to be on the lookout for asthma symptoms in children with food allergies, as poorly controlled asthma is a risk factor for severe food-induced allergic responses and anaphylaxis.