According to a study published today in eLife, grouping of pathogen-recognizing proteins on immunological T cells may be crucial for determining whether someone has ever been infected.

The strength and targets of a person’s T-cell response to infection or vaccination are more difficult to evaluate for researchers, but the findings point to a potential new strategy. Tests detecting antibodies against a pathogen are frequently used to discover symptoms of a prior infection.

One day, this patient data might be helpful for diagnosing illnesses, directing care, or advancing the investigation and creation of fresh remedies and vaccinations.

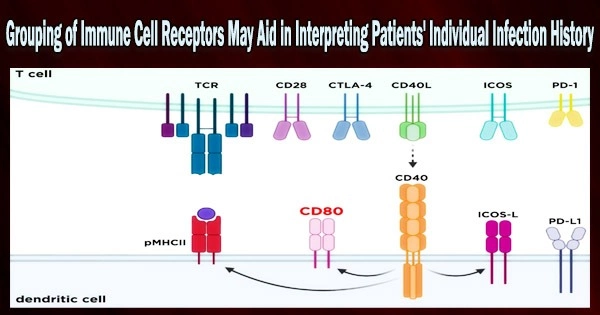

Immune T cells help the body find and destroy harmful viruses and bacteria. Receptors are proteins on the outside of T cells that enable the T cells to identify and destroy human cells that have been infected by particular viruses.

“While the abundance of specific receptors could provide clues about past infection, the enormous molecular diversity of T-cell receptors makes it incredibly challenging to assess which receptors recognise which pathogens. Not only is each pathogen recognised by a distinct set of receptors, but each individual develops a personalised set of receptors for each pathogen,” explains first author Koshlan Mayer-Blackwell, Senior Data Scientist at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, US.

“We developed a new computational approach that allows us to find similarities among pathogen-specific T-cell receptors across individuals. Ultimately, we hope this will help develop signatures of past infection despite the enormous diversity of T-cell receptors.”

Our software provides flexible tools that will enable scientists to analyse and integrate the rapidly growing libraries of T-cell receptor sequencing data that are needed to identify the features of pathogen-specific T-cell receptors. We hope it will open new opportunities not only to identify patients’ immunological memories of past infections and vaccinations but also to predict their future immune responses.

Andrew Fiore-Gartland

The team tested their approach using data from the immuneRACE study of T-cell receptors in patients with COVID-19. They were able to create 1,831 T-cell receptor groupings using their novel software for quickly comparing huge sets of receptors based on similarities in the receptors’ amino acid sequences that suggest they have comparable activities.

The team discovered that in a separate group of COVID-19 patients, the common molecular patterns linked to receptor groupings were more reliably detected than individual receptor sequences that were previously hypothesized to recognize components of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. This resulted in a significant advancement over previous methods.

“Our study introduces and validates a flexible approach to identify sets of similar T-cell receptors, which we hope will be broadly useful for scientists studying T-cell immunity,” Mayer-Blackwell says. “Grouping receptors together in this way makes it possible to compare responses to infection or vaccination across a diverse population.”

The team has developed free, customizable software called tcrdist3 to assist other researchers use this method to produce T-cell biomarkers using their own data.

“Our software provides flexible tools that will enable scientists to analyse and integrate the rapidly growing libraries of T-cell receptor sequencing data that are needed to identify the features of pathogen-specific T-cell receptors,” concludes senior author Andrew Fiore-Gartland, Co-Director of the Vaccines and Immunology Statistical Center at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. “We hope it will open new opportunities not only to identify patients’ immunological memories of past infections and vaccinations but also to predict their future immune responses.”