Lava flowed into the moon’s crust four billion years ago, engraving the man in the moon we see today. However, the volcanoes may have left a much colder legacy: ice. A new study reveals that two billion years of volcanic eruptions on the moon may have resulted in the formation of multiple short-lived atmospheres containing water vapor. Researchers write in the May Planetary Science Journal that the vapor could have been carried through the atmosphere before settling as ice at the poles.

Since the discovery of lunar ice in 2009, scientists have discussed the probable sources of water on the moon, which include asteroids, comets, and electrically charged atoms carried by the solar wind. Or, possibly, the water originated on the moon itself, as vapor belched by the rash of volcanic eruptions from 4 billion to 2 billion years ago.

“How those volatiles [such as water] got there is a tremendously interesting subject,” says Andrew Wilcoski, a planetary scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder. “We still don’t have a decent idea of how many there are or where they are.”

Wilcoski and his colleagues chose to begin by investigating the possibility of volcanism as a source of lunar ice. Eruptions occurred approximately once every 22,000 years during the height of lunar volcanism. Based on samples of ancient lunar lava, the researchers estimated that the eruptions produced up to 20 quadrillion kilos of water vapor in total, or the volume of nearly 25 Lake Superiors.

The findings support a long-held belief that ice dominates at the poles because it becomes trapped in cold traps so frigid that it remains frozen for billions of years. There are some places at the lunar poles that are as cold as Pluto.

Margaret Landis

Some of this vapor would have been lost to space as a result of sunlight breaking down water molecules or the solar wind blowing the molecules away from the moon. However, at the polar extremes, some may have frozen to the surface as ice. But for that to happen, the pace at which the water vapor condensed into ice had to be faster than the rate at which the vapor exited the moon. The team calculated and compared these rates using a computer simulation. The simulation took into account variables such as surface temperature, gas pressure, and the loss of some vapor due to frost.

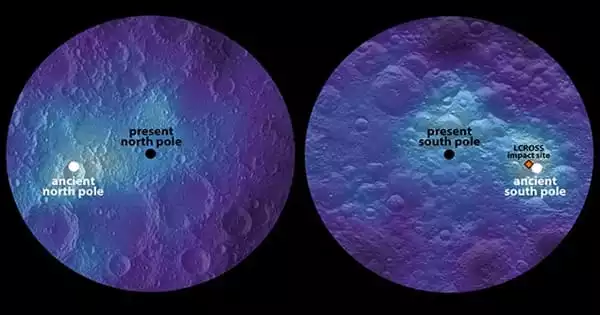

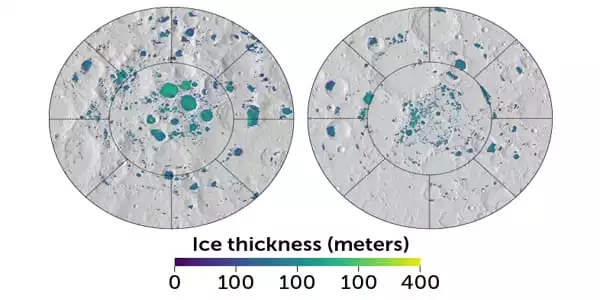

The scientists discovered that approximately 40% of the total emitted water vapor may have accumulated as ice, with the majority of that ice accumulating near the poles. Over billions of years, part of that ice would have melted and escaped into space. The team’s modeling forecasts the volume and distribution of remaining ice. And it’s not a tiny amount: Deposits might reach hundreds of meters in thickness at their thickest point, with the south pole being roughly twice as icy as the north pole.

The findings support a long-held belief that ice dominates at the poles because it becomes trapped in cold traps so frigid that it remains frozen for billions of years. “There are some places at the lunar poles that are as cold as Pluto,” says planetary scientist Margaret Landis of the University of Colorado Boulder.

Water vapor derived from volcanoes, on the other hand, is likely to be dependent on the presence of an atmosphere, according to Landis, Wilcoski, and their colleague Paul Hayne, also a planetary scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder. An atmospheric transit mechanism would have allowed water molecules to circulate around the moon while simultaneously making escape into space more difficult. According to the new calculations, each eruption created a fresh atmosphere that lasted roughly 2,500 years before dissipating until the next explosion 20,000 years later.

This element of the tale intrigues Parvathy Prem, a planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, who was not engaged with the research. “It’s a fascinating work of imagination…. How can you create atmospheres from the ground up? “And why do they occasionally vanish?” she wonders. “One method to find out is to look at the polar ice caps.”

If lunar ice was belched out of volcanoes as water vapor, the ice may have retained a memory of that distant past. Sulfur on polar ice, for example, would suggest that it originated from a volcano rather than, say, an asteroid. Future moon missions will drill for ice cores to confirm the origin of the ice.

When considering lunar resources, it is critical to look for sulfur. According to the experts, these water reserves could one day be harvested by astronauts for water or rocket fuel. “That’s a fairly crucial thing to know if you plan on bringing a straw with you to the moon,” Landis says, if all of the lunar water is tainted with sulfur.