The relationship between exercise endurance, cold tolerance, and cellular maintenance in flies is an intriguing topic of study in genetics and physiology. Specific genes and genetic pathways that appear to have a role in these interrelated features have been uncovered by scientists.

As the days grow shorter and chillier in the northern hemisphere, people who prefer to exercise in the mornings may find it more difficult to get out of bed. A recent study published in PNAS reveals a protein that, when lacking, makes exercising in the cold more difficult – at least in fruit flies.

While examining metabolism and the effects of stress on the body, researchers from the University of Michigan Medical School and Wayne State University School of Medicine identified the protein in flies, which they dubbed Iditarod after the historic long-distance dog sled race across Alaska.

They were particularly interested in autophagy, a physiological process in which damaged sections of cells are eliminated from the body. They discovered a candidate for regulating the crucial housekeeping procedure while screening the fly genome.

We believe that exercise helps clean the cellular environment through autophagy. When you are exercising hard, there is damage to the muscle and some of the mitochondria will malfunction. The autophagy process becomes activated to clean up any damaged organelles or toxic byproducts, and Idit gene seems important in this process.

Jun Hee Lee

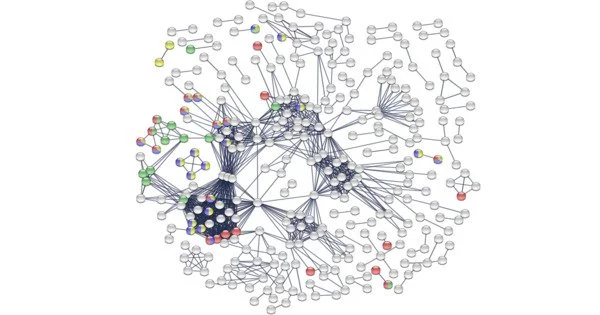

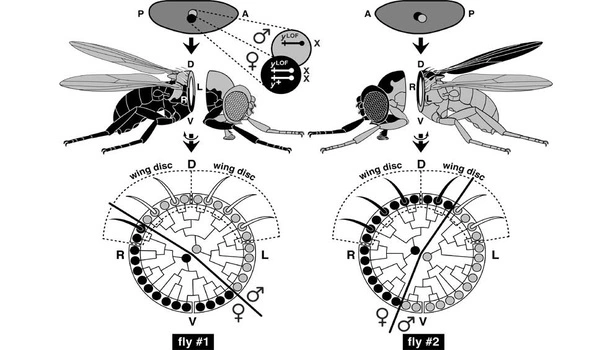

They established the link between autophagy and Iditarod, or Idit, by modifying the genetic composition of certain flies to increase autophagy in their eyes. Flies with excessive autophagy experienced significant cell death, resulting in obvious eye degeneration. The Idit gene was inactivated, which restored normal eye anatomy, demonstrating that the Idit gene is involved in the autophagy process.

The team’s next step was to hunt for a homolog, or similar gene, in humans.

“When we queried this gene in the human genome, a gene called FNDC5, which is a precursor to the protein irisin, was the top hit,” said Jun Hee Lee, Ph.D., from the University of Michigan’s Department of Molecular and Integrative Physiology.

Previous research has shown irisin to be an important hormone involved in producing musculoskeletal and other benefits of exercise in mammals, as well as playing a role in adaptation to cold temperatures. Lee’s lab had an existing interest in exercise as a mild form of bodily stress.

“We realized this gene may be also important for exercise and if so, we should be able to detect a similar physiological effect in flies,” said Lee.

The researchers used a type of fly cliff climber that capitalizes on the insect’s propensity to climb higher out of a test tube while working with Dr. Robert Wessells’ team at Wayne State University, who devised a revolutionary approach to educate fruit flies.

They discovered that flies bred to lack the Idit gene had reduced exercise endurance and did not improve as expected following training. In addition, irisin is known to upregulate thermogenic processes in mammals, which is important for cold resistance. Flies lacking Idit were similarly unable to endure cold.

According to Lee, this gene family, which is found in both invertebrates and mammals, appears to have been preserved throughout evolution and plays an important purpose.

“We believe that exercise helps clean the cellular environment through autophagy,” he stated. “When you are exercising hard, there is damage to the muscle and some of the mitochondria will malfunction,” he explained. “The autophagy process becomes activated to clean up any damaged organelles or toxic byproducts, and Idit gene seems important in this process.”

Lee aims to relate this research to their earlier work on exercise and physiological stress in the future.