Specialists at the School of Veterinary Medicine (CVM) have recognized a significant pathway that uncovers why a few warm-blooded creatures, similar to people, canines, and felines, routinely foster mammary disease while others, like ponies, pigs, and cows, seldom do.

They utilized an uncommon way to reveal a piece of that riddle—why cells in certain species become destructive—which they portrayed in a paper distributed in Correspondences Science in October.

The disclosure depends on a past finding that gives hints about the sub-atomic systems at play. Mammary undifferentiated organisms from certain species with low rates of mammary malignant growth utilize a cycle called apoptosis to obliterate cells with damaged DNA. Interestingly, numerous species with a high frequency of mammary disease fix their DNA-harmed cells, leaving them vulnerable to the expected dangerous transformations.

“Our research is novel because we used healthy cells rather than cancer cells to try to understand how a microRNA can prevent cells from becoming cancerous. There are still many details to work out. This is a minor but significant piece of the puzzle.”

said Rebecca Harman, the study’s lead author and a research support specialist at the Baker Institute for Animal Health.

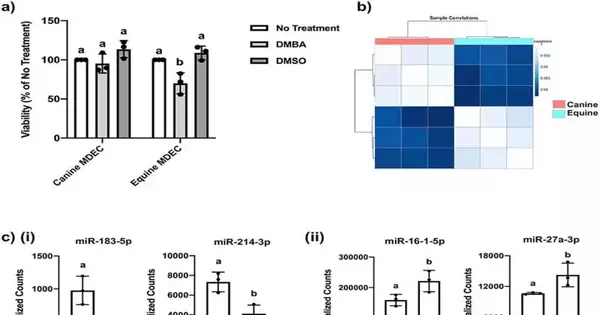

In the review, specialists zeroed in on the job of microRNA-214-3p, a microRNA that is known to play a part in managing apoptosis or cell obliteration. They looked at the microRNA-214-3p capabilities in undifferentiated cells from ponies, which seldom foster mammary disease, and from canines, which routinely do. They found that microRNA-214-3p is communicated at low levels in horse cells yet at more significant levels in canine cells, and that this low microRNA-214-3p articulation advances the apoptosis that obliterates horse cells with harmed DNA.

“Our examination is novel since we worked with sound cells, not disease cells, attempting to comprehend how a microRNA can keep cells from becoming destructive,” said Rebecca Harman, the review’s lead creator and an exploration support expert at the Cook Organization for Creature Wellbeing. “There are, as yet, many subtleties to be worked out. This is a little piece of the riddle; however, it’s a significant piece.”

Harman works in the lab of Dr. Gerlinde Van de Walle, the Alfred H. Caspary Teacher, and is the head of the pastry specialist Foundation for Creature Wellbeing. They worked together intimately with Praveen Sethupathy, teacher of physiological genomics and seat of the Division of Biomedical Sciences at CVM, who concentrates on the job of microRNAs in creature and human illnesses, including malignant growth.

“MicroRNAs are by and large understudied in veterinary tumors,” Sethupathy said. “This work addresses and expands on the accentuation on near malignant growth science at Cornell.”

After their underlying discoveries, the exploration group led a second trial to expand the declaration of miRNA-214-3p in horse cells misleadingly. This prompted the restraint of apoptosis: when miRNA-214-3p articulation expanded, DNA-harmed horse cells were more averse to being annihilated.

Leading comparative exploratory methodologies in numerous species is one more significant part of this examination, Van de Walle said.

“The most intriguing piece of this sort of exploration is contrasting species that get the infection with those that don’t,” she said. “With this relative methodology, you can find new data that you would miss from checking just a single animal variety out. Also, we are bound to have the option to apply our discoveries to human infection.”

More information: Rebecca M. Harman et al, miRNA-214-3p stimulates carcinogen-induced mammary epithelial cell apoptosis in mammary cancer-resistant species, Communications Biology (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s42003-023-05370-4