Bipolar disorder can cause dramatic swings in mood, activity level, and energy. A study that found alterations in the brains of people at risk of developing bipolar disorder provides new expectations for early intervention. A brain imaging research of young adolescents at high risk of developing bipolar disorder discovered for the first time evidence of deteriorating connections between crucial parts of the brain in late adolescence.

Until now, medical researchers understood that bipolar disorder was associated with decreased connectivity between brain networks involved in emotional processing and thinking, but how these networks originated prior to the diagnosis remained a mystery.

Researchers from UNSW Sydney, the Hunter Medical Research Institute (HMRI), the University of Newcastle, and international institutions published a study in The American Journal of Psychiatry that found evidence of these networks diminishing over time in young adults at high genetic risk of developing bipolar disorder, which has important implications for future intervention strategies.

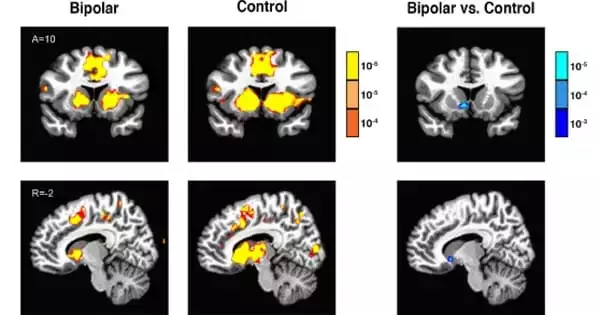

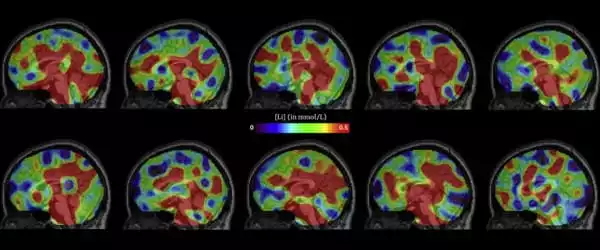

Over a two-year period, the researchers employed diffusion-weighted magnetic imaging (dMRI) technology to scan the brains of 183 people. They compared the progression of alterations in brain scans of persons with a high hereditary risk of getting the illness to a control group of people with no risk during a two-year period.

Our research truly helps us understand the pathway for people who are at risk of bipolar disorder. We now have a far better understanding of what’s going on in the brains of young individuals as they grow up.

Professor Philip Mitchell

People who have a parent or sibling who has bipolar illness are at high genetic risk and are 10 times more likely to develop the condition than those who do not have a close familial link. The researchers observed a decline in connection between regions of the brain devoted to emotion processing and cognition throughout the two years between scans in 97 persons with a high genetic risk of bipolar disorder.

The opposite was observed in the control group of 86 persons with no family history of mental illness: strengthening in the neural connections between these same regions as the adolescent brain evolves to become more skilled at the cognitive and emotional reasoning required in adulthood.

Scientia Professor Philip Mitchell AM, a practising academic psychiatrist at UNSW Medicine & Health, says the findings raise fresh ideas regarding therapy and intervention in young people at risk of developing bipolar illness.

“Our research truly helps us understand the pathway for people who are at risk of bipolar disorder,” he explains. “We now have a far better understanding of what’s going on in the brains of young individuals as they grow up.”

Prof. Mitchell explains that as a therapist and researcher, he knows firsthand how young people’s life may be flipped upside down when they suffer their first manic episode.

“We see a lot of bright, talented adolescents who are having a great time in life, and bipolar disorder can be a major hindrance to what they want to achieve. With our new understanding of what happens in the brain as at-risk youth reach adulthood, we can design new intervention measures to either stop the disorder in its tracks or lessen the effect of the sickness.”

Mental image

Professor Michael Breakspear, who led the team at HMRI and the University of Newcastle that carried out the analysis of the dMRI scans, says the study illustrates how advances in technology can potentially bring about life-changing improvements to the way that mental illnesses can be treated.

“Relatives of people with bipolar disorder, particularly siblings and children, frequently inquire about their own future risk, and this is a matter of great personal worry,” he says.

“It’s also a problem for their doctors, because bipolar disorder has serious medication consequences. This study is a significant step toward having imaging and genetic diagnostics that can assist identify those who are likely to develop bipolar disorder before they acquire the condition’s severe and stressful symptoms. This would put psychiatry more in line with other disciplines of medicine where screening tests are routine.”

The experts emphasize that further research is needed before changing current treatment methods. It would also be impractical and expensive to examine all persons with a genetic risk of developing bipolar disorder to see if the brain is displaying symptoms of impaired connectivity.

“The main conclusion of our study is that there is progressive change in the brains of young people at risk of bipolar disorder, indicating how crucial intervention tactics may be,” Prof. Mitchell says. “If we can intervene early, whether through psychological resilience training or drugs, we may be able to prevent this path toward significant brain alterations.”

Dr. Gloria Roberts, a postdoctoral researcher with UNSW Medicine & Health who has been working on the project since 2008, has noticed how fresh onsets of mental illness in kids at risk of developing bipolar disorder can have a major impact on psychosocial functioning and quality of life.

“By improving our understanding of the neurobiology of risk as well as resilience in these high-risk individuals, we will be able to intervene and improve the quality of life in the most vulnerable individuals.”

As a result of the new findings, the researchers intend to conduct a third follow-up scan on study participants. They are also in the early phases of establishing online programs to help young people develop resilience while also teaching them how to manage anxiety and depression, which they think will minimize their risks of developing bipolar illness.