Driving home from work, Kristin Herman was grasping her steering wheel hard. It was mid-April, and one of the district’s heaviest rainstorms since Hurricane Ida was rushing through Bucks County, Pennsylvania.

With the downpour descending, Herman, 37, couldn’t resist the opportunity to contemplate the nerve-racking drive she’d made using her family’s Downingtown home months earlier to get away from Ida’s flooding. With her better half, Ross, at work and unfit to return home on the roadway, she had escaped with their two youthful little girls to a friend’s home.

“By a wide margin, the most obviously terrible drive of my life. “Icurrently do not at any point in the future need to drive in a downpour,” said Herman, who depicted herself as “white-knuckled” that April day. “Driving in downpours currently is terrible.”

The memory of that evening was enduring. Nowadays, when she can, Herman telecommutes to try not to go in this terrible climate. Ross has become more reluctant to leave his family when he works evening shifts.

That sort of nervousness is only one way Herman and her family actually feel the impact of Hurricane Ida, whose leftovers obliterated quite a bit of their split-level home when it crushed the locale in September. It took a drawn-out inn stay, long periods of work, and about $85,000 to fix their home.

They’re in good company to feel some trepidation. As environmental change supercharges serious climate occasions, occasional nervousness is turning out to be more far and wide. From Californians concerned about high winds spreading wildfires to Texans concerned about potential winter freezes, a growing number of Americans are moved by climate-related injury and tension, particularly in the Philadelphia area.

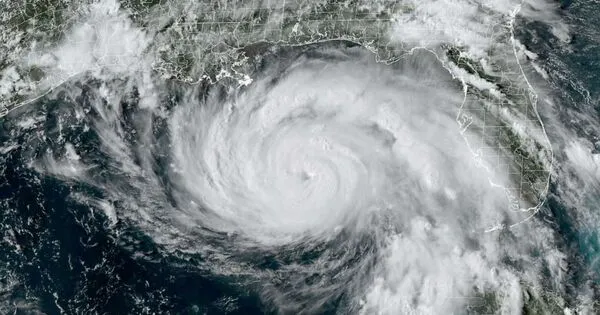

Here, it implies wrestling with post-awful pressure after Ida and other late tempests. With the Atlantic storm season beginning—it started Wednesday—Ida’s landfall nine months prior stays fresh in the personalities of those most severely impacted.

“We’re all still grieving from it. Of course, the kids who went through this still have stress and anxiety… from being rescued by a boat and witnessing your community flood away.”

Nikki Milholin, whose street in Montgomery County’s Mont Clare was flooded by Ida.

“We are in general actually faltering from it,” said Nikki Milholin, whose road in Mont Clare, Montgomery County, was crushed by Ida’s flooding. “The children who went through this still, obviously, have injuries and tension from being safeguarded by a boat and watching their area essentially wash away.”

Beginning this month, more rain is coming — the yearly danger elevated by the impacts of environmental change, which can reinforce tropical storms and improve the probability of flooding.

The current year’s typhoon season is supposed to be just about as serious as or more regrettable than last year, with above-typical quantities of hurricanes conceivable in this locale once more.

What’s more, the temperatures and precipitation in the Philadelphia locale have a likelihood of being higher than typical for June, July, and August, according to the National Weather Service gauge the week before.

After a climate debacle, individuals can encounter a wide scope of post-horrible pressure responses, including bitterness, despondency, and nervousness that the fiasco could repeat. Commemorations of the occasion or the beginning of the following season can set off pressure, said Karla Vermeulen, delegate overseer of the Institute for Disaster Mental Health at State University of New York at New Paltz.

Vermeulen said that post-horrible pressure responses are not equivalent to post-horrendous pressure issues. A clinical condition, however, can in any case cause enduring pressure.

Pennsylvania has seen other horrendous typhoons, yet a considerable lot of the district’s occupants portrayed Ida’s flooding and cyclones as the most terrible in their memory. What’s more, many say exactly the same thing: It will repeat.

“The term that individuals are beginning to use for it is ecoanxiety,” Vermeulen said. “It’s simply that feeling of fear, that feeling of being wild, being powerless.”

At the point when Kimberly Capparella and her better half drive between Norristown and King of Prussia, they get the extension over the Schuylkill and recollect how high the stream was the previous fall. They experienced about $50,000 in damage to their Norristown home, which has been in Capparella’s family for generations.

“At the point when we go over through King of Prussia and I see the water, we simply take a gander at one another,” said Capparella, 51. “What’s more, I’m very much like, goodness my golly. It’s dependably toward the rear of your head, but you make an effort not to consider it. “

In any case, the impacts will wait. Capparella’s 13-year-old daughter has experienced nervousness. Milholin stated that her children used to shudder when it rained, and that her child now asks if there is flooding whenever it rains.The flood has appeared in the Hermans’ girls’ school fine art, and at whatever point something gets lost at home, the young ladies, 5 and 8, think it was lost in the flood.

At Legal Aid of Southeastern Pennsylvania, Sara Planthaber has worked with many clients who endured Ida. She’s seen injuries locally.

“Individuals are like, ‘I didn’t rest the previous evening; we had a tempest,'” said Planthaber, a staff lawyer who has dealt with around 50 Ida cases. “Each and every time it downpours, individuals get restless and anxious.”

The fear of a recurring event also affects those who provide various types of assistance to disaster victims.Legitimate Aid staff are now talking about the certainty of future tempests.

“We as a whole realize this will repeat,” Planthaber said. “I’m most anxious about places that got hit truly hard and are probably going to get hit hard once more.”

Around 46% of Americans said they had by and by encountered the impacts of environmental change in a 2021 Yale Program on Climate Change Communication review, and 65% said they stressed over an Earth-wide temperature boost.

As individuals in certain regions feel the danger of serious tempests or discharges all the more, Vermeulen and her partners have started talking about how environmental change might be impeding the regular recuperation cycle.

“There is certainly no way to refocus and have a good sense of security once more, feel like you can let down your watchfulness once more, and that is debilitating,” she said.

For Milholin and her better half, this was the second time they’d had to deal with a significant flood: they lost their home to one in 2006. They revamped the house and raised it, but it actually took on around eight feet of water in September.

“Having done this two times currently,” said Milholin, 42, of encountering floods, “dealing with trauma is hard. I might just, by and by, want to see psychological wellness be essential for a fiasco crisis reaction. “

Part of the continuous tension, many said, is wrestling with the unusualness of tempests and people’s absence of command over what occurs — a feeling that you want to get ready for something you may not really have the option to plan for.

The Hermans depicted a “consistent longing” to safeguard their home and their family—they invested a ton of energy pondering relief measures for their property. However, it’s accompanied by a feeling of not exactly knowing what to do.

“At the point when it downpours, you simply need to live with that trepidation until it passes,” Herman said. “To really have that enormous obliteration and to understand that each project worker who came through said, ‘Prepare. This is simply going to happen more frequently. ‘”

Vermeulen suggested that individuals do as much as could reasonably be expected to get ready—have a clearing plan, a go sack, and a cutoff time for choosing whether to empty or sanctuary set up—and afterward perceive that it’s difficult to control what else occurs.

“Give your best to get ready and then, afterward, give yourself credit for that,” she said. Then, [don’t] simply be centered totally around the gamble. In any case, it is difficult by far. “

The evening of Ida, Milholin utilized what she calls her instruments to assess the danger — water measures along the rivulet, the National Weather Service, the NOAA site — yet even those didn’t help this time. Unexpectedly, the river level was higher than anticipated and recently continued to rise.

“I’m an information is-power sort of individual, so I attempt to keep steady over it, but I actually couldn’t get ready last time,” Milholin said. “I’m completely mindful that it’s not [that it] may work out, it will repeat.”