When Joan Casey lived in northern California, she experienced frequent power outages during the wildfire season. While trusting that the power would return, she considered how the multi-day power outages impacted a local area’s wellbeing.

“For me, it was a bother; however, for certain individuals, it very well may be dangerous,” said Casey, presently an associate teacher in the College of Washington’s Branch of Natural and Word-Related Wellbeing Sciences. “Assuming you had an uncle that had an electric heart siphon, fundamentally, his heart wouldn’t work without power. If you don’t have access to electricity, you’ll need to go to the emergency room after using a backup battery for eight hours. The situation is extremely risky.”

Casey has the answers, years later. A study that looked at three years of power outages across the United States and was published on April 29 in the journal Nature Communications found that Americans who are already feeling the effects of climate change and health disparities are concentrated in four areas—Louisiana, Arkansas, central Alabama, and northern Michigan—and that they are most vulnerable to being affected by a prolonged blackout.

The discoveries could assist with forming the fate of neighborhood energy foundations, particularly as environmental change increases and the American power matrix keeps on maturing. Casey hopes that federal agencies will use the newly published findings to target energy upgrades, as the Inflation Reduction Act of last year included billions of dollars to revamp energy systems.

“We check the weather forecast and decide whether to bring an umbrella or stay at home. However, considering being prepared for an outage when one of these events occurs is a new factor to consider.”

Joan Casey, now an assistant professor in the University of Washington’s Department of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences.

The review is the primary area-level investigation of blackouts, which the national government reports just at the state level. Researchers face a dilemma as a result: a Washington state outage that has been reported to the federal government could occur in Seattle, Spokane, or somewhere in between, making it difficult to identify the specific affected population.

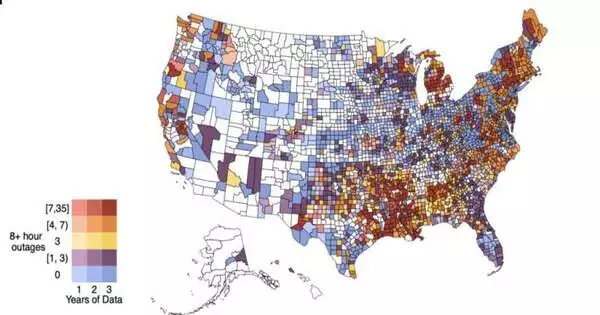

Between 2018 and 2020, more than 231,000 nationwide power outages lasting more than an hour were discovered by Casey and her team. 17,484 of them lasted at least eight hours, which is widely considered to be relevant to medicine.

At least one electrical outage in the majority of counties lasted longer than eight hours. These areas were generally moved to the south, upper east, and Appalachia.

Then, specialists saw how blackouts covered serious weather. They needed to realize which climate occasions are probably going to cause a blackout and what parts of the U.S. are most frequently hit with a power outage-causing storm.

They discovered that heavy precipitation in a specific region increases the likelihood of a power outage by five times. A 14-fold increase in the likelihood of a power outage is caused by tropical cyclones, storms with high winds that originate over tropical oceans. And a tropical cyclone with a lot of rain on a hot day, like a hurricane that hits the Gulf Coast every fall? They make blackouts multiple times more probable.

“We see climate projections and choose whether or not to bring an umbrella or remain at home,” Casey said. “However, pondering being ready for a blackout when one of these occasions is moving through is another component to consider.”

The issue of equity came next. Communities that would likely be particularly vulnerable during a prolonged power outage were identified by Casey’s team using a combination of socioeconomic and medical factors. The communities that experienced frequent power outages in addition to high social vulnerability were identified by the researchers using that data.

A guide to those districts shows a splendid group in Louisiana and Arkansas, with additional bunches in focal Alabama and northern Michigan. The country’s unavoidable transformation in its energy infrastructure presents the greatest opportunity to improve public health, particularly in those locations.

Casey stated, “It’s exciting any time we can identify another factor that we can intervene on to get closer to health equity.” In the coming decades, I believe there will be a lot of change, especially in the way our energy systems are set up. It’s a huge chance to include equity in every conversation and discuss the steps we’ll take to make the world a different place in two decades.

This review started while Casey was a teacher in Columbia College’s Postal Service School of General Wellbeing. Vivian Do, the first author, Heather McBrien, Nina Flores, Alexander Northrop, Jeffrey Schlegelmilch, and Mathew Kiang at Stanford University, as well as Vivian Do at Columbia University, are the other authors.

More information: Vivian Do et al, Spatiotemporal distribution of power outages with climate events and social vulnerability in the USA, Nature Communications (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-38084-6