Our recollections are rich and exhaustive; we can clearly review the shade of our home, the design of our kitchen, or the front of our most loved bistro. How the cerebrum encodes this data has long astounded neuroscientists.

In another Dartmouth-drove study, specialists recognized a brain coding component that permits the exchange of data to and fro between perceptual locales and memory regions of the mind. The outcomes are distributed in Nature Neuroscience.

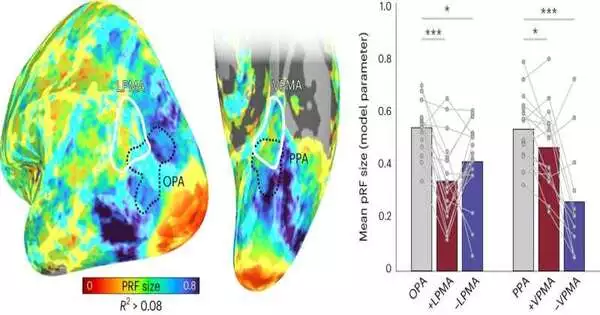

Before this work, the exemplary comprehension of cerebrum association was that perceptual districts of the mind address the world “for what it’s worth,” with the cerebrum’s visual cortex addressing the outer world in view of how light falls on the retina, “retinotopically.” Conversely, it was believed that the cerebrum’s memory regions address data in a theoretical configuration, deprived of insights concerning its actual nature. Nonetheless, as per the co-creators, this clarification neglects to consider that as data is encoded or reviewed, these locales may, as a matter of fact, share a typical code in the cerebrum.

“We found that memory-related mind regions encode the world like a ‘visual negative’ in space,” says co-lead creator Adam Steel, a postdoctoral specialist in the Branch of Mental and Cerebrum Sciences and individual in the Neukom Organization for Computational Science at Dartmouth. “What’s more, that ‘negative’ is essential for the mechanics that move data all through memory and among perceptual and memory frameworks.”

“We discovered that memory-related brain areas encode the world in space like a ‘photographic negative,’ and that this ‘negative’ is part of the mechanics that move information into and out of memory, as well as between perceptual and memory systems.”

says co-lead author Adam Steel, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences and fellow in the Neukom Institute for Computational Science at Dartmouth.

In a progression of trials, members were tested on discernment and memory while their mind movement was recorded utilizing a useful, attractive reverberation imaging (fMRI) scanner. The group recognized a contradicting push-pull-like coding system, which oversees the connection among perceptual and memory regions in the cerebrum.

The outcomes showed that when light raises a ruckus around town, the visual region of the cerebrum answers by expanding their movement to address the example of light. Memory regions of the cerebrum likewise answer visual feelings; be that as it may, dissimilar to visual regions, their brain action diminishes while handling a similar visual example.

The co-creators report that the review has three surprising discoveries. The first is their disclosure that a visual coding rule is saved in memory frameworks.

The second is that this visual code is topsy-turvy in memory frameworks. “At the point when you see something in your visual field, neurons in the visual cortex are driving while those in the memory framework are calmed,” says senior creator Caroline Robertson, an associate teacher of mental and cerebrum sciences at Dartmouth.

Third, this relationship flips during memory review. “Assuming you shut your eyes and recollect that visual upgrades in a similar space, you’ll flip the relationship: your memory framework will be driving, stifling the neurons in perceptual districts,” says Robertson.

“Our outcomes give a reasonable illustration of how shared visual data is involved by memory frameworks to get reviewed recollections and out of concentration,” says co-lead creator Ed Silson, an instructor of human mental neuroscience at the College of Edinburgh.

Pushing ahead, the group intends to investigate how this to and fro between discernment and memory might add to difficulties in clinical circumstances, remembering for Alzheimer’s.

More information: Adam Steel et al, A retinotopic code structures the interaction between perception and memory systems, Nature Neuroscience (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41593-023-01512-3

Journal information: Nature Neuroscience