Openness to injury can be extraordinary, and analysts are becoming familiar with how awful mishaps may actually change our cerebrums. Yet, these progressions are not a direct result of actual injury; rather, the cerebrum seems to overhaul itself after these encounters.

Understanding the components engaged with these progressions and how the cerebrum finds out about a climate and predicts dangers and wellbeing is a focal point of the ZVR Lab at the Del Monte Organization for Neuroscience at the College of Rochester, which is driven by colleague teacher Benjamin Suarez-Jimenez, Ph.D.

“We’re learning more about how traumatized people learn to discern between what’s safe and what’s not. Their brain is providing us with information about what might be going wrong in specific mechanisms impacted by trauma exposure, particularly when emotion is involved.”

Suarez-Jimenez,

“We’re learning more about how people who have been exposed to injury determine what is safe and what isn’t.””Their cerebrum is giving us knowledge into what may be turning out badly in unambiguous components that are influenced by injury openness, particularly when feeling is involved,” said Suarez-Jimenez, who started this work as a post-doctoral individual in the lab of Yuval Neria, Ph.D., teacher at Columbia College Irving Clinical Center.

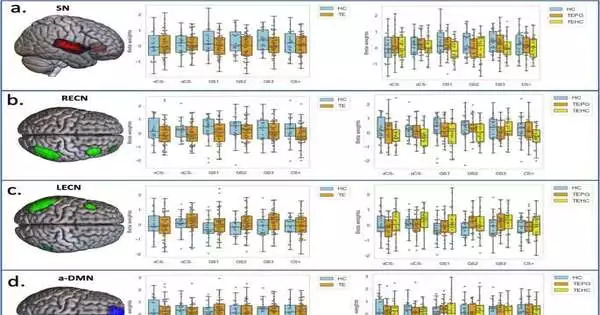

Their research, which was recently published in Correspondences Science, discovered changes in the remarkable quality organization—a component of the cerebrum used for learning and endurance—in individuals exposed to injury (with and without psychopathologies, for example, PTSD, melancholy, and tension).

Utilizing fMRI, the specialists kept movement in the minds of members as they took a gander at various estimated circles—jjust a single size was associated with a little shock (or danger). Along with the advancements in the exceptional quality organization, analysts discovered another distinction—this one inside the injury uncovered a strong gathering.They discovered that individuals who presented to injury without psychopathologies were compensating for changes in their mind processes by attracting the leader control organization, one of the mind’s dominant organizations.

“Knowing what to look for in the mind when someone is injured could essentially propel medicine,” said Suarez-Jimenez, a co-first author of this paper with Xi Zhu, Ph.D., a clinical neurobiology right-hand teacher at Columbia.”For this situation, we know where a change is occurring in the mind and how certain individuals can function around that change.” “It is a marker of versatility.”

Adding the component of feeling

The possibility of danger can alter how someone who has been injured reacts.According to a new study published in Sadness and Tension, this is the case in people suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).Suarez-Jimenez, his kindred co-creators, and senior creator Neria found that patients with PTSD can finish a similar job as somebody without openness to injury when no inclination is involved. Be that as it may, when the feeling conjured by a danger was added to a comparable errand, those with PTSD had more trouble recognizing the distinctions.

The group used the same strategies as in the previous trial: different circle sizes, with one size associated with a danger as a shock.Using fMRI, researchers discovered that people with PTSD had less movement between the hippocampus (a region of the brain responsible for feeling and memory) and the notability organization (a component used for learning and endurance).

They also discovered less movement between the amygdala (another region associated with feeling) and the default mode organization (a region of the cerebrum that activates when someone isn’t focused on the rest of the world).These findings mirror a PTSD patient’s inability to distinguish contrasts between the circles.

“This lets us know that patients with PTSD have issues separating just when there is a personal part.” “For this situation, which is aversive, we actually need to affirm, assuming that this is valid for different feelings like trouble, disdain, joy, and so on,” said Suarez-Jimenez. “In this way, it is possible that in reality, feelings overburden their mental capacity to separate between security, risk, or award.” “It overgeneralizes towards risk.”

“Taken together, discoveries from the two papers, emerging from a… study expecting to uncover the brain and conduct systems of injury, PTSD, and strength, help to broaden our insight about the impact of injury on the cerebrum,” said Neria, the lead PI on this review.

“PTSD is driven by striking brokenness in mind regions imperative to fear handling and reaction.” “My lab at Columbia and Dr. Suarez-Jimenez’s lab at Rochester are determined to advance neurobiological research that will meet the need for advancement with new and better medicines that can truly target distorted fear circuits.”

Suarez-Jimenez will keep investigating the cerebrum components and the various feelings related to them by utilizing all the more genuine circumstances with the assistance of computer-generated reality in his lab. He must understand whether these systems and changes are well defined for a risk and whether they grow to set related processes.

More information: Xi Zhu et al, Sequential fear generalization and network connectivity in trauma exposed humans with and without psychopathology, Communications Biology (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s42003-022-04228-5

Journal information: Communications Biology