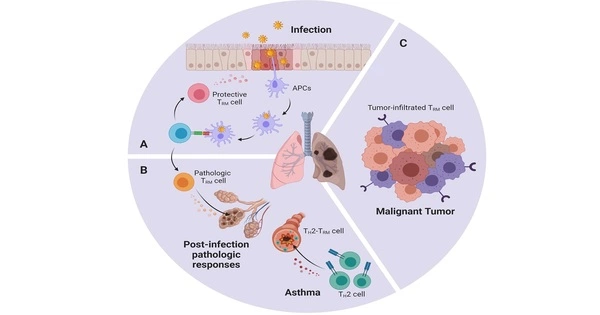

The respiratory system, particularly the lungs, is predominantly affected by influenza, a viral infection. The influenza virus infects and replicates in the epithelial cells lining the airways and lungs when it enters the respiratory tract.

Trinity College Dublin researchers uncovered several novel and surprising ways for viral RNA and influenza virus to be detected by human lung cells, which could have consequences for treating people infected with such viruses.

Influenza viruses continue to be a major hazard to human health, causing severe symptoms in children, the elderly, and immunocompromised persons, resulting in annual epidemics that imperil between 3 and 5 million people with severe illness and cause 290,000 to 650,000 fatalities globally.

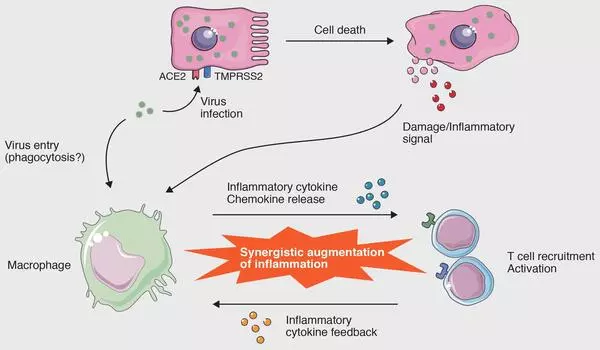

These viruses predominantly reproduce in respiratory epithelial cells, causing cell damage and death. Scientists have discovered that these epithelial cells are not merely passive barriers that cannot be attacked, but rather play an important role in activating the antiviral immune response.

We were able to ask some fundamental questions about how our bodies respond to RNA viruses like influenza and SARS-CoV-2 by forming an EU-wide network of scientists with different expertise in immunology and virology.

Professor Bowie

However, our understanding of the mechanism underlying that response has been quite restricted up to this point. Some answers have now emerged as a result of the work of PhD student Coralie Guy in the research team of Andrew Bowie, Professor of Innate Immunology in Trinity’s School of Biochemistry and Immunology.

The researchers discovered that viral RNA and influenza viruses activate two distinct molecular pathways in which specific proteins initiate chain reactions that result in the processing of two proteins known as “gasdermin D” and “gasdermin E” in such a way that they form membrane pores in epithelial cells.

These pores allow the release of special agent “cytokines” charged with sparking the immune system into life, and also cause death of the cells which prevents the virus spreading.

To assess the importance of this finding, the team suppressed the formation of the gasdermin pores to see what would happen, and this resulted in increased replication of influenza viruses, underlining how important these gasdermins are in the antiviral response.

The research has just been published in the journal iScience. Speaking about the research and its implications, Professor Bowie, who is based in Trinity’s Biomedical Sciences Institute, said:

“We were able to ask some fundamental questions about how our bodies respond to RNA viruses like influenza and SARS-CoV-2 by forming an EU-wide network of scientists with different expertise in immunology and virology.”

“We discovered that very little was understood about the initial reaction to viruses at the moments when our lungs first come into contact with a virus. We were able to make several major discoveries thanks to Coralie’s study, which highlighted previously unknown features of the immune response to influenza, which we will now build on to see how relevant they are to other viral diseases of the lung, such as SARS-CoV-2 and RSV.”