A group of specialists, including a Virginia District College teacher, has found uncommon ancient instruments produced using the bones of birds going back over 12,000 years, as per discoveries distributed Friday in the diary Logical Reports.

The seven aerophones, or flutes, that were discovered at the Eynan-Mallaha site in northern Israel belong to the Natufians. These people lived between 13000 and 9700 B.C., and they were some of the last people who hunted and gathered food in the Levant, or Near East, at that time.

1,112 bones belonging to 59 different bird species were found at the site, and Tal Simmons, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of Forensic Science at VCU’s College of Humanities and Sciences, was a co-author of the Scientific Reports paper. Thanks to her research, the team was able to learn when the site’s nomadic hunters and gatherers lived there and which species’ bones were frequently found there.

“All seven were purposefully created by grooving and rotating small stone blades into the long bones of two types of birds—the Eurasian teal and the Eurasian coot. They all have tiny wear, indicating that they were used or played with.”

Tal Simmons, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of Forensic Science.

“Bone “flutes” or “aerophones” are known from other archaeological sites around the world, but they are extremely uncommon and have mostly been found in Europe. Simmons stated, “These are the first to ever be identified from the Near East and date to approximately 12,000 years ago.” The flutes really utter the hints of different flying predators that were pursued at the site.”

One of seven small bone aerophones made of waterfowl that were found at the Final Natufian site of Eynan-Mallaha It looks like a notched flute (like an Andean quena). The instrument’s play-holes (in green), marks (in blue), mouthpiece, distal part, and red ochre residues are shown in detail. Credit: Davin et al., 2023

This is the first time a prehistoric sound instrument from the Near East has been found. It is also the oldest instrument from any ancient civilization that mimics a bird’s call.

One aerophone still has its finger holes and mouthpiece intact. Simmons described the flute’s sound as “a high-pitched screeching call, very much like a smaller bird of prey up in the treetops” when played.

“Every one of the seven was deliberately made by scoring and rotational scratching with little stone edges into the long bones of two sorts of birds — the Eurasian greenish blue and the Eurasian fogy. Simmons stated, “They all exhibit microscopic wear, indicating that they were used or played.” They are also one of a kind because the sound they make is very similar to that of the kestrel and sparrowhawk, two specific birds of prey that were hunted by the people who lived at the location where they were found.”

The aerophones may have been used for hunting, communication, or making music in spiritual practices, according to the researchers.

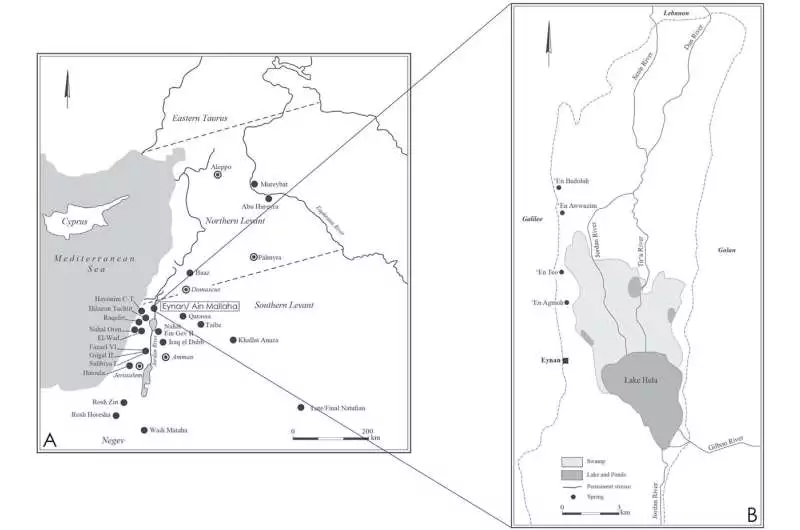

A Guide of the Dispersion of Last Natufian Destinations in the Levant quite a while back B: Detail of the place of Eynan-Mallaha in the Houla Valley of Northern Israel. Credit: Davin et al., 2023.

“Because these are some of the earliest aerophones, it sheds light on the role of music in Natufian culture—and possibly on the relationship of Natufian peoples with birds of prey.” Simmons said.

It could have been used as a duck call to try to entice the birds into being hunted. However, it could also have been an attempt to communicate with these birds of prey through spiritual means. The disproportionate number of raptor talons found in archaeological bird-bone assemblages indicates that they were significant to Natufian and earlier Levantine cultures. These could have been “totem” animals or even ritual “jewelry” worn by prehistoric people.”

On the Givat Ram campus of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the aerophones are currently housed in the zoological collections.

More information: Laurent Davin et al, Bone aerophones from Eynan-Mallaha (Israel) indicate imitation of raptor calls by the last hunter-gatherers in the Levant, Scientific Reports (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-023-35700-9