Restricting how much coal nations can consume is viewed as an earnest need for limiting worldwide warming. All things considered, coal is the most carbon-rich of every petroleum product, and its burning has contributed the most to planetary warming. Without precedent for worldwide discussions, arbitrators consented to “stage down” coal use to forestall a worldwide temperature climb surpassing 1.5°C in the 2021 Glasgow Environment Agreement.

Coal’s power in environmental exchanges is halfway a direct result of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which has conceived pathways to stopping warming at 1.5°C. These logical evaluations focus on the quick elimination of coal consumption, not just for the fuel’s carbon power and the need to head off CO2 gathering in the air, but additionally to energize the accessibility of cost-effective options such as sunlight-based and wind farms.

Scientists additionally stress the significance of decarbonizing the power area right off the bat in the green shift to empower different areas, like vehicles and industry, to run on clean power from the matrix.

This puts the onus on specific countries to decrease discharges quicker than others. The majority of global coal consumption can be traced back to emerging and developing countries such as China and India.Here, huge armadas of power stations and processing plants depend on coal, which is modest and bountiful compared with other petroleum products. By outlining the solution for environmental change as one where coal is eliminated first, these nations should focus on quickly decarbonizing in the following 10 years.

In our new paper distributed in Nature Environmental Change, we feature two issues with the most widely distributed pathways to keeping away from devastating environmental change. In the first place, it is improbable that coal-subordinate nations will actually want to discard the fuel as quickly as these pathways set out.

Furthermore, as this is the situation, other non-renewable energy sources, to be specific, oil and gas, should be eliminated all the more quickly to make up for coal’s slower exit. This would shift responsibility for mitigating environmental change to developed countries.

As far as possible, get rid of coal.

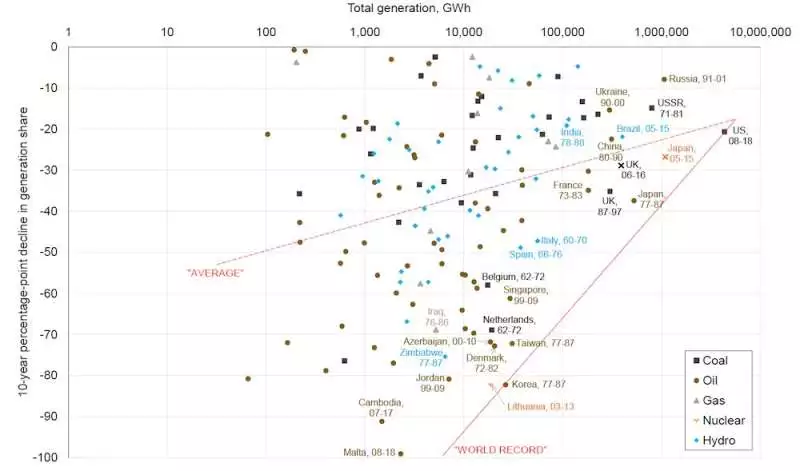

We analyzed how much coal use is supposed to fall in the displayed pathways to 1.5 °C with the quickest power changes that have occurred throughout the course of recent years, with all energies and in all nations.

These changes are displayed in the figure underneath and mirror a scope of drivers, for example, strategy reactions to the 1970s oil cost emergency and political occasions like conflicts, sanctions, and the breakdown of the Soviet Union. The red line labeled “world record” shows the quickest pace that could be achieved with the political will to sanction aggressive strategies.

Korea’s exit from oil somewhere between 1977 and 1987 was one of the quickest energy changes ever. Coal-subordinate nations are supposed to move much quicker today.

In view of the displayed pathways from the IPCC, we gauge that coal power should be progressively eliminated in India, China, and South Africa over two times as quickly as any verifiable power change for power frameworks of similar size. This is probably not going to be reachable or OK in any significant coal-subordinate emerging nation.

A more plausible path to coal disposal could be to use the goals set out by the Controlling Past Coal Partnership (PPCA), a global alliance of nations formed in 2017.The PPCA favors a separate timetable for leaving coal influence, with rich nations going first by 2030 and the remainder of the world by 2050.

These objectives reflect how agricultural nations are more subject to coal and have less cash to put resources into green progress, yet bear less authentic obligation regarding causing environmental change.

This disparity in speed would place a few nations, including China, at the extremes of verifiable change.As a result, it would provide them with a difficult, but conceivable, path to decarbonization.This path would result in developed countries reducing fossil fuel byproducts roughly half as quickly as paths without the more appealing dispersion of endeavors proposed by the PPCA.

This alters the story from the progressive environment’s highest points: nations that were created, not those that were created, are the ones that should accomplish other things in the present moment to restrict warming.

It likewise has significant ramifications for oil and gas. In all nations, oil and gas creation should fall even in distributed pathways to as opposed to expanding as most nations plan.

However, when the world stages out coal at the PPCA speed, oil and gas should be gradually transitioned away from correspondingly faster. This distinctively affects various nations. For instance, combined oil creation by the US from 2020 to 2050 is 20% lower than in a 1.5°C pathway without the separated endeavors proposed by the PPCA.

Restricting environmental change requires deliberately getting rid of every one of the three non-renewable energy sources: coal, oil, and gas. Our examination finds that the models and strategies discussed depend a lot on slowing down coal, particularly in coal-subordinate non-industrial nations.

All things considered, a more attractive and more reasonable equilibrium of relief endeavors is required, and that implies more accentuation on wiping out oil and gas. It also implies increased effort from the global north, even as all nations, including those in the global south, work to phase out coal power as soon as possible.

More information: Greg Muttitt et al, Socio-political feasibility of coal power phase-out and its role in mitigation pathways, Nature Climate Change (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41558-022-01576-2