In another paper distributed in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution, researchers from the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and accomplices in the U.K., Germany, and the U.S. have decoded the world’s most seasoned plant genome, utilizing Neolithic-time watermelon seeds gathered at an archeological site in the Sahara Desert in Libya.

The review joined parts of an archeological basis with a state-of-the-art genomics examination to reveal new insight into the taming of the watermelon and how our precursors drank the famous natural product’s old family members. Shockingly, proof proposes the Neolithic Libyans had a preference for the watermelon’s seeds — a nearby delicacy actually drank today — yet kept away from the natural product’s harsh tasting tissue.

It is estimated that in excess of 200 million tons of tamed watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) are grown worldwide consistently, with the yield being among the top 10 most significant in Central Asia. The red-fleshed organic product is by and large acknowledged to have begun in Africa, where a direct relative (C. lanatus subsp. cordophanus) was no doubt originally tamed in the Nile Valley and what is now North Sudan. Yet, the revelation in the mid 1990s of assumed watermelon seeds at the Neolithic site of Uan Muhuggiag in Libya kept on baffling researchers.

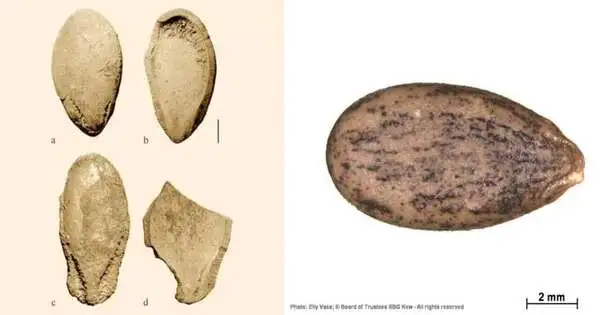

To more readily comprehend the watermelon’s excursion from wild plant to tamed crop, the analysts gathered and examined many watermelon and watermelon family members’ seeds from RBG Kew’s Herbarium assortments. They likewise got and concentrated on seed fossils from Libya and Sudan, radiocarbon dated (C-14) to more than a long time ago, separately.

“Seed morphology, particularly of old seeds, was just insufficient to properly identify which species early Neolithic immigrants in Libya were utilizing,”

Dr. Susanne S. Renner at Washington University in St. Louis,

Dr. Susanne S. Renner at Washington University in St. Louis, who along with Dr. Guillaume Chomicki at Sheffield University, drove the review, said, “Seed morphology, particularly of old seeds, was just lacking to recognize which species those Neolithic pilgrims in Libya were utilizing dependably.”

The researchers had the option to settle the secret when they examined the seeds’ genome and recuperated extended lengths across all chromosomes—perhaps the most seasoned genome at any point kept in such detail from a plant whose age has been checked utilizing radiocarbon dating examinations. They likewise sequenced the genomes of many watermelon examples in Kew’s Herbarium assortments, some of which were first gathered in the mid-nineteenth century.

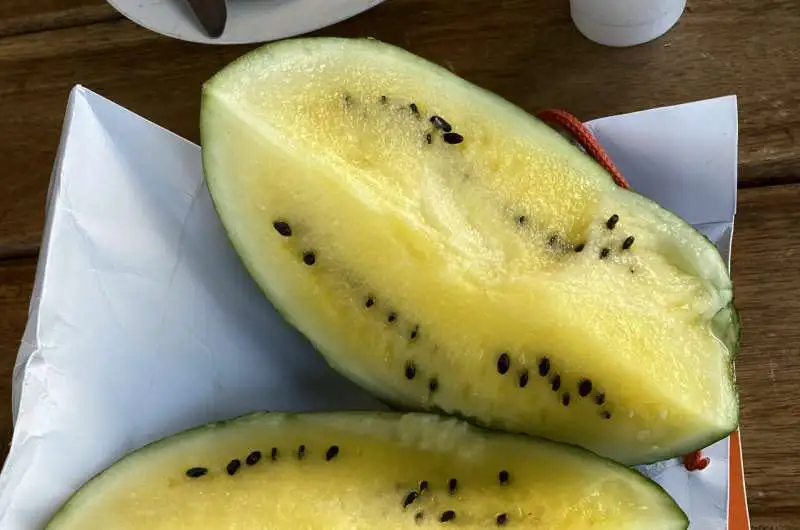

The tissue and seeds of a yellow watermelon, which has a sweet mash yet lower lycopene content (a splendid red carotenoid hydrocarbon and shade that gives different organic products their particular red tone), RBG KEW, OSCAR ALEJANDRO PEREZ ESCOBAR

The review’s discoveries show the Neolithic Libyans gathered or even developed a harsh-tasting variety of watermelon, rather than the sweet-tasting yield of today. This new knowledge was confirmed with teeth marks found on the most seasoned seeds gathered in Sudan by Dr. Philippa Ryan, a postdoctoral scientist at Kew and co-creator of the review.

Before the examination of the genome, the analysts couldn’t recognize the Libyan examples from the other seven known species in the Citrullus sort. Their sub-atomic outcomes presently show that the seeds came from a watermelon relative known as Egusi watermelons (Citrullus mucosospermus) from West Africa. These natural products are harsh and unpalatable when eaten raw because of the compound cucurbitacin in their tissue and are rather reaped for their seeds, which are utilized in West African stews and soups, comparable in size and flavor to pumpkin seeds.

Ryan said, “It’s a major shock to find that, as opposed to being an old watermelon, the Libyan seed was a completely unique tamed Citrullus, while the pharaonic-period Sudanese seed had atomic DNA from both the harsh Egusi and the sweet watermelon. This proposes that by a later time span, an intriguing blend of tamed Citrullus assortments were developed along the Nile Valley for their seeds—close by probably the sweet watermelon. “

By better understanding the hereditary cosmetics of these old organic products, the scientists desire to portray the watermelon’s taming. Yet, the exploration has more broad and current ramifications too. Graphing the trading of qualities during that time might assist researchers with pinpointing good hereditary attributes that support strength during dry spells, illness, and bugs.

Dr. Oscar A. Perez Escobar, Research Leader in Kew’s Integrated Monography Team and first creator, said, “It is a striking accomplishment to have found out such a huge amount about the mysterious previous existence of these old seeds through their DNA. Without this hereditary code, which we figured out how to get exhaustively, we could never have found that a major part of the DNA of these seeds is detectable in Egusi gourds (C. mucospermus) and not in sweet watermelon. One more striking disclosure conveyed through their DNA is that these old seeds of Egusi watermelon probably hybridized and traded qualities with sweet watermelons millennia prior, despite the fact that it is as yet unclear to us the directionality of such a quality stream. “

The review was done as a team with Dr. Guillaume Chomicki at Sheffield University and Professor Susanne S. Renner at Washington University in St. Louis, as well as the Antonelli Lab research group, specialists in developmental science and biogeography.

Perez Escobar said, “Our review is an extraordinary illustration of what plant assortments addressing millennia of developmental and social history can do at whatever point they are utilized in multidisciplinary research. The information assets we created and our revelation on the connections that Egusi and sweet watermelons have supported for centuries, including the trading of qualities through ages, is of interest for sweet watermelon crop improvement programs at whatever point specific qualities are looked for, e.g., illness and bug opposition. “

More information: Oscar A Pérez-Escobar et al, Genome Sequencing of up to 6,000-Year-Old Citrullus Seeds Reveals Use of a Bitter-Fleshed Species Prior to Watermelon Domestication, Molecular Biology and Evolution (2022). DOI: 10.1093/molbev/msac168

Journal information: Molecular Biology and Evolution“Seed morphology, particularly of old seeds, was just insufficient to properly identify which species early Neolithic immigrants in Libya were utilizing,” says the study’s lead author.