Past neuroscience studies propose that while concluding their next activities, mice and different rodents will generally replay previous results of comparative circumstances in their minds, which is reflected in a quick enactment of specific cerebrum districts in succession. As of late, a few examinations have kept comparative replay-related cerebrum action in the human mind by utilizing imaging strategies.

A study by UCL researchers looked into the possibility that this rapid “replay” of positive and negative outcomes from the past could predict how people will act in a situation where they could lose or gain money. Their findings, which were published in Nature Neuroscience, suggest that humans mentally represent the worst-case scenario that could result from their decision when approaching or avoiding a situation. This suggests that there may be a link between replay in the brain and the planned behavior of humans.

One of the researchers who carried out the study, Jessica McFadyen, told Medical Xpress, “This work was inspired by the many new discoveries that have been made about “replay” in the brain.” Rodents will generally replay ways towards remuneration (arranging where to go), yet in addition, they will more often than not replay ways that could prompt an electric shock (arranging where not to go). So, what takes place when we are unsure whether a path will result in reward or punishment? I was intrigued by this.

“When we’re uncertain, it’s difficult to decide whether to stay (avoid) or go (approach), and it’s possible that replay in the brain could explain how we eventually make up our minds,”

Jessica McFadyen, one of the researchers who carried out the study,

Recent research conducted by McFadyen, Yunzhe Liu, and Raymond J. Dolan was primarily focused on determining how the human brain replays various paths when the outcome is unclear. They specifically looked at situations where people might be indecisive about whether to approach or avoid a particular path, or the “approach-avoidance conflict.”

McFadyen stated, “When we’re uncertain, choosing whether to stay (avoid) or go (approach) is hard, and it’s possible that replay in the brain could explain how we eventually make up our mind.” We tested this hypothesis by utilizing a method of brain imaging known as magnetoencephalography, in which a machine mounted on the head is used to detect the minute electric currents that flow through human neurons.

Magnetoencephalography permits specialists to unequivocally quantify eruptions of movement in various regions of the mind and when they happen. It was specifically used by McFadyen and her colleagues to measure the very short bursts of brain activity that occur during replay, about 40 milliseconds apart.

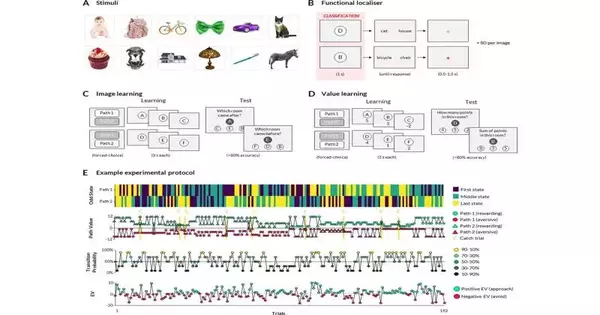

They kept these eruptions of movement in 25 members who were approached to participate in a straightforward picture-based game. The participants in this game were given a variety of scenarios in which they had to choose whether to proceed along a particular path or not.

McFadyen explained, “Participants learned which sequences would end with positive points (bonus money) or negative points (no bonus money).” “The paths were just sequences of images.” The fact that participants might not be able to get where they wanted to go if they chose to approach There was always a chance—for instance, a 30% chance—that they would be led down a more perilous path. We recorded the brain activity that we were most interested in, namely that associated with replay during approach-avoidance conflict, as participants considered whether or not to take the risk.

The researchers analyzed the participants’ brain recordings using machine learning to identify which of the previously presented images were replayed in the brain while the participants made a new decision. To put it another way, when the participants were first shown an image, the models they used detected the reactivation of previously recorded sequences of brain activity.

By dissecting these outcomes in combination with the choices that members made (i.e., whether they drew closer or stayed away from a given circumstance), McFadyen and her partners were then ready to figure out the things that were being replayed before members chose to approach or keep away from a given situation.

According to McFadyen, “our biggest finding was that humans play out the worst-case scenario.” The tendency was for participants to replay (or, more accurately, “simulate”) the paths that led to the desired but forgone reward when they ultimately decided to avoid them altogether. Then again, assuming that members in the long run chose to approach and face the challenge, they would in general replay ways, prompting the dreaded adverse result. This kind of counterfactual reasoning could be a way for the cerebrum to ensure we remember elective results.”

This team’s findings shed new light on the types of past experiences that people tend to replay in their minds before deciding whether to approach or avoid a given circumstance. They might help us learn more about the connections between replay and decision-making in the future, and they might also help us learn more about avoidant behaviors that are linked to anxiety disorders and other psychiatric conditions.

McFadyen added, “There are many places this research could take us.” Since it is difficult to obtain reliable measurements even with machine learning, one option would be to further investigate how to better measure replay in the human brain. The relationship between replay and negative simulations of the future and the past, which are major contributors to depression and anxiety, could then be further investigated. We can better guide mental health treatments if we have a better understanding of where these simulations take place in the brain and how spontaneous or controllable they are.”

More information: Jessica McFadyen et al, Differential replay of reward and punishment paths predicts approach and avoidance, Nature Neuroscience (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41593-023-01287-7