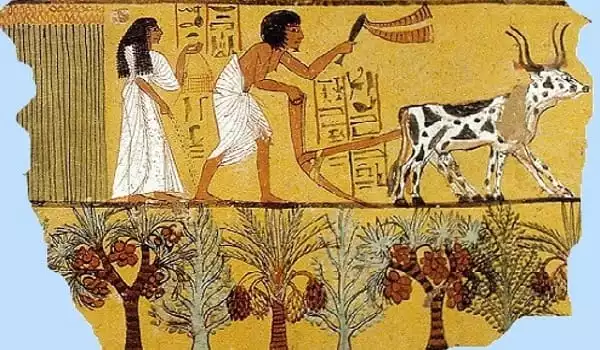

Mesopotamia, the cradle of civilisation, was the birthplace of many significant innovations and discoveries. Agriculture got its start here. Because of the fertile soil between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, irrigation and cultivation were prevalent in this area. Agriculture enabled humans to dwell in the same place for longer periods of time without having to rely on hunting.

Researchers from Rutgers University have discovered the oldest definitive evidence of broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum) in ancient Iraq, challenging our view of humanity’s early agricultural activities. Their findings were published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Mesopotamia, which is concentrated in modern-day Iraq, is considered the birthplace of civilisation. While humans were present in the region as early as 12,000 B.C.E., historians believe significant civilizations emerged in Mesopotamia between 4,000 and 3,000 B.C.E. During this time period, Mesopotamia’s development was aided by a number of geographical elements, including rivers and rich fields.

Overall, the presence of millet in ancient Iraq during this earlier time period challenges the accepted narrative of agricultural development in the region as well as our models for how ancient societies provisioned themselves.

Elise Laugier

“Overall, the presence of millet in ancient Iraq during this earlier time period challenges the accepted narrative of agricultural development in the region as well as our models for how ancient societies provisioned themselves,” said Elise Laugier, an environmental archaeologist and National Science Foundation postdoctoral fellow in the School of Arts and Sciences at Rutgers University-New Brunswick.

Broomcorn millet is a “very vigorous, quick-growing, and diverse summer crop” that was first cultivated in East Asia, according to Laugier. The researchers examined microscopic plant remains (phytoliths) at Khani Masi, a site from the mid-late second millennium BCE (c. 1500-1100 BCE) in Iraq’s Kurdistan area.

“The existence of this East Asian grain in ancient Iraq demonstrates the interwoven character of Eurasia at the time, contributing to our understanding of early food globalization,” Laugier added. “Our discovery of millet, and hence evidence of summer farming methods, forces us to rethink the capacity and durability of the agricultural systems that maintained and provisioned Mesopotamia’s early towns, governments, and empires.”

For environmental and historical reasons, the discovery of broomcorn millet in ancient Mesopotamia was remarkable. Researchers previously believed that millet was not produced in Iraq until the establishment of the 1st millennium BCE imperial irrigation networks. Millet grows best in the summer, but Southwest Asia has a wet winter and dry summer climate, therefore agricultural production is nearly exclusively focused on winter crops like wheat and barley.

Agricultural output is supposed to have been the foundation for Mesopotamian towns, states, and empires. Because of the researchers’ new evidence that crops and food were grown during the summer months, previous studies have likely significantly underestimated the capacity and durability of ancient agricultural food-system communities in semi-arid settings.

Mesopotamia’s land was exceptionally fruitful, which prompted humanity to settle in the region and begin farming. People were residing in the “Fertile Crescent” area as early as 5,800 B.C.E. to take advantage of the fertile soil. The richness of the soil was due to runoff from adjacent mountains, which dumped nourishing silt onto the river floodplain on a regular basis. This region extended northward from modern-day Kuwait and Iraq to Turkey. Prior to the establishment of Mesopotamia, neolithic humans were primarily hunters and gatherers with sporadic cultivation. Because of Mesopotamia’s exceptional productivity, humanity were able to settle in one location to farm.

The new study is also part of a growing body of archaeological evidence that, in the past, agricultural innovation was a local initiative, implemented as part of local diversification strategies long before it was used in imperial agricultural intensification regimes – new information that could influence how agricultural innovations are implemented today.

“Although millet is not a common or preferred grain in semi-arid Southwest Asia or the United States today,” Laugier explained, “it is nevertheless common in other parts of Asia and Africa. Millet is a tough, fast-growing, low-water-required, and nutritious gluten-free grain with a lot of potential for improving the resilience of our semi-arid food systems. Agricultural innovators of today should explore investing in more diversified and robust food systems, much as people in ancient Mesopotamia did.”

Laugier, a visiting scientist at Rutgers who received her Ph.D. and began her research on this topic at Dartmouth College, stated that the research team hopes to make phytolith analysis more common in the study of ancient Iraq because it can challenge assumptions about the region’s agricultural history and practice.