The Hunga Volcano eruption in Tonga on January 15, 2022, continues to set records. A new study claims that the eruption resulted in a “supercharged” thunderstorm with the strongest lightning ever recorded. During the eruption, the researchers discovered that there were nearly 200,000 lightning flashes in the volcanic plume, peaking at more than 2,600 flashes per minute.

The submarine volcano erupted in the southern Pacific Ocean, releasing a 58-kilometer-high plume of ash, water, and magmatic gas. Scientists were able to learn a lot about the scale of the eruption from the towering plume, but satellites couldn’t see the vent, making it harder to follow the eruption’s progress.

Scientists now have access to high-resolution lightning data from four distinct sources—never before used all together—to peer into that plume, revealing new phases of the eruption’s life cycle and gaining insight into the bizarre weather it produced.

“This eruption triggered a supercharged thunderstorm, the likes of which we’ve never seen. These findings demonstrate a new tool we have to monitor volcanoes at the speed of light and help the USGS’s role to inform ash hazard advisories to aircraft.”

Alexa Van Eaton, a volcanologist at the United States Geological Survey who led the study.

Alexa Van Eaton, a volcanologist at the United States Geological Survey who led the study, stated, “This eruption triggered a supercharged thunderstorm, the likes of which we’ve never seen.” These findings demonstrate a brand-new instrument for monitoring volcanoes at the speed of light and support the USGS’s role in advising aircraft of ash hazards.

Geophysical Research Letters is a journal that publishes high-impact, short-format reports with immediate repercussions for the entire Earth and space sciences.

According to Van Eaton, the storm formed as a result of a highly energetic magma expulsion striking the shallow ocean. Seawater rose into the plume after being vaporized by molten rock, resulting in electrifying collisions between hailstones, supercooled water, and volcanic ash. A lightning storm was in the making.

The researchers estimated the heights of lightning flashes by combining data from radio waves and light sensors. Nearly 500,000 electrical pulses made up just over 192,000 flashes, peaking at 2,615 per minute during the eruption. In the Earth’s atmosphere, some of this lightning reached unheard-of heights of 20 to 30 kilometers (12 to 19 miles).

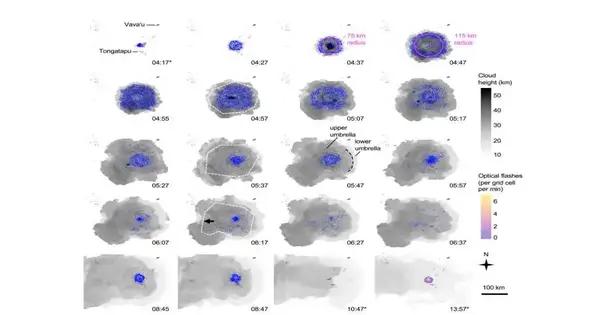

On January 15, 2022, the eruption at Tonga’s Hunga Volcano saw more than 200,000 lightning flashes, represented by blue dots. New insights into the progression of the eruption were provided by new analyses of the intensity of the lightning during the eruption, which revealed that the volcanic storm was the strongest ever recorded. Credit: Letters of the Geophysical Research Society DOI: Van Eaton stated, “With this eruption, we discovered that volcanic plumes can create the conditions for lightning far beyond the realm of meteorological thunderstorms we have previously observed.” 10.1029/2022GL102341 It ends up that volcanic emissions can make more outrageous lightning than some other sort of tempest on The planet.”

The lightning revealed not only how long the eruption lasted but also how it changed over time.

Van Eaton stated, “The eruption lasted much longer than the hour or two initially observed.” For at least 11 hours, the January 15 activity produced volcanic plumes. We really weren’t able to figure that out until we looked at the lightning data.”

The researchers observed four distinct eruptive phases characterized by fluctuating plume heights and lightning rates. According to Van Eaton, the insights gleaned from connecting the intensity of lightning to eruptive activity can improve monitoring and forecasting of aviation-related risks during a large volcanic eruption, such as the formation and movement of ash clouds.

Finding reliable information about volcanic plumes at the beginning of an eruption is difficult, especially for submarine volcanoes that are far away. Early detection is improved to keep people and aircraft out of harm’s way by utilizing all long-range observations, including lightning.

Van Eaton stated, “It wasn’t just the lightning intensity that drew us in.” The lightning rings that expanded and contracted in concentric rings around the volcano also baffled her and her colleagues. We were blown away by these lightning rings’ size. There has never been anything comparable in meteorological storms, and we have never seen anything like that before. Single lightning rings have been noticed, however, not products, and they’re small by examination.”

Again, intense turbulence at high altitude was to blame. Like dropping pebbles in a pond, the plume injected so much mass into the upper atmosphere that it caused ripples in the volcanic cloud. The lightning moved outward in 250-kilometer-wide rings that appeared to “surf” these waves.

As if all of that weren’t enough to make this eruption fascinating, it also exemplifies the phreatoplinian type of volcanism, in which a lot of magma erupts through water. In the past, this kind of eruption was only known from the geological record, and no modern instrumentation had ever been used to observe it. All that was altered by the Hunga eruption.

Van Eaton observed, “It was like unearthing a dinosaur and seeing it walk around on four legs.” It takes your breath away in a way.”

More information: Alexa R. Van Eaton et al, Lightning Rings and Gravity Waves: Insights Into the Giant Eruption Plume From Tonga’s Hunga Volcano on 15 January 2022, Geophysical Research Letters (2023). DOI: 10.1029/2022GL102341