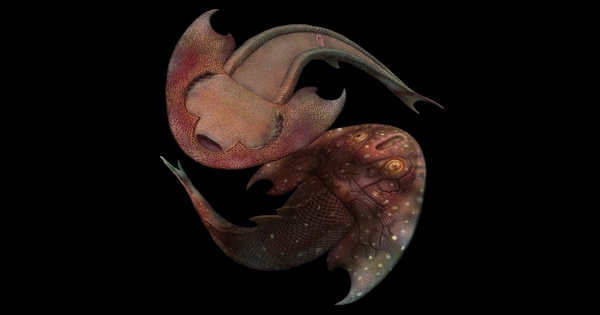

The ancestor of all vertebrates, including fish, reptiles, and humans, had a big mouth but no anus. Saccorhytus, named after the sack-like features created by its elliptical body and large mouth, existed 540 million years ago. It was identified using microfossils discovered in China.

It was about a millimetre in size, lived between grains of sand on the sea floor, and had a large mouth in comparison to the rest of its body, according to researchers. They also believe the creature had a thin, relatively flexible skin, a muscle system capable of contractile movements, and the ability to move by wriggling.

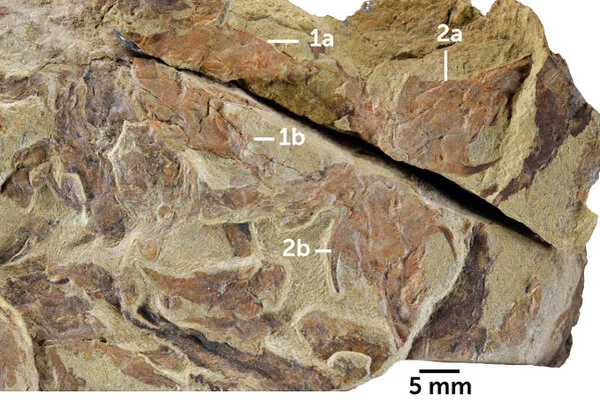

A newly discovered treasure trove of ancient fish fossils discovered in southern China is providing insight into the earliest history of jawed vertebrates, which include 99 percent of all living vertebrates on Earth, including humans. The fossil site, which dates from 439 million to 436 million years ago, contains a surprising number of previously unseen small, toothy, bony fish species.

The diversity of the fossils at this one site not only fills a glaring gap in the fossil record, but also highlights the oddity that such a gap exists. These discoveries confirm what we’ve been arguing for” for years based on smaller bits of fossils.

Michael Coates

The diversity of the fossils at this one site not only fills a glaring gap in the fossil record, but also highlights the oddity that such a gap exists, according to researchers who published their findings in Nature. “These discoveries confirm what we’ve been arguing for” for years based on smaller bits of fossils, says Michael Coates, a paleobiologist at the University of Chicago who was not involved in the research.

Previously, genetic analyses pointed to the early Silurian Period as a time of rapid diversification of jawed vertebrates. However, the toothy fishes appeared to have left few traces in the fossil record. Instead, according to the fossil record, jawless fishes appeared to rule the seas at the time. And the jawed fishes that have been preserved were mostly chondrichthyans, the ancient cartilaginous ancestors of modern sharks and rays.

The Chongqing Lagerstätte — paleontologists’ word for a rich assemblage of diverse species all preserved together at one site — “fundamentally changes that picture,” write paleontologist You-an Zhu of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing and colleagues in the study. The site is teeming with toothy, bony fishes, particularly armored placoderms, but bears just one chondrichthyan.

Fish were the first creatures to develop a backbone, approximately 480 million years ago. According to genetic studies, those fish developed jaws around 450 million years ago, allowing them to chomp each other. However, the earliest complete fossils of such jawed fish appear relatively late in the fossil record, around 425 million years ago. Jawed fishes were a global phenomenon by the Devonian Period, which lasted from 419 million to 359 million years ago, earning the era the moniker “Age of Fishes.”

The discovery also hints that the ancestor of both types of jawed fishes, bony and cartilaginous, could have arisen earlier than thought, Coates says. It’s possible that the last common ancestor of modern jawed vertebrates appeared during the Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event, which began around 471 million years ago. To date, scientists have found only three varieties of fish body fossils dating to that time period, all jawless, finless, and “vaguely resembling a super-sized armor-plated tadpole,” Coates adds.