Specialists at Eötvös Loránd College have examined whether the impression of time changes with age and, provided that this is true, how and why we see the progression of time in an unexpected way. Their review was distributed in logical reports.

Time can pull pranks on us. Many of us were duped into thinking that those long summers when we were kids felt a lot longer than similar 3 months do now as adults. While we can debate why one summer is longer than another and how the perception of time can pack and enlarge spans based on various factors, we can easily set up a trial to acquire bits of knowledge.

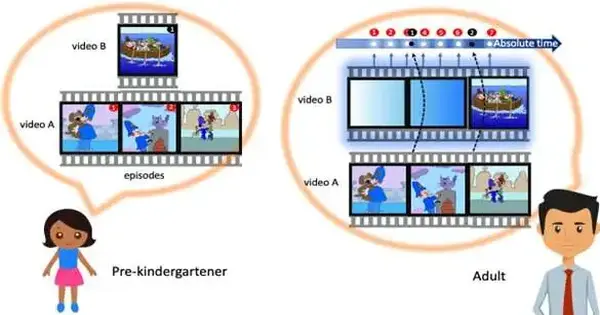

The specialists recently did that. They asked what eventfulness means for our span gauges while examining various achievements during our mental turn of events. They separated three age groups—4-5, 9-10, and 18 and older—and made them watch two one-minute recordings.The two recordings were removed from a famous vivified series and adjusted for visual and acoustic highlights, with the exception of one component: eventfulness.

One video consisted of a quick progression of occasions (a police officer protecting creatures and capturing a criminal), and the other was a dreary and dull grouping (six obscure detainees getting away on a paddling boat). The experts played the two clasps in a reasonable amount of time, focusing on the exciting first. Subsequent to watching the two recordings, they posed just two inquiries: “Which one was longer?” and “Might you at any point show the lengths with your arms?” In any case, simple questions for a four-year-old.

The results revealed areas of strength for each age group, but for pre-kindergarteners, the opposite was true.

While more than 2/3 of preschoolers saw the exciting video as longer, about 3/4 of the grown-up bunch had an equivalent outlook on the unremarkable video. The center group expressed a similar but more moderate inclination than the adults.By considering the center gathering (9–10-year-olds), the affectation point could be assessed around the age of 7.

As to arm-spread direction and distance, there was a rising pattern of utilizing level arm spreading with age. While prekindergarten-age kids utilized 50/50 vertical and flat signals, by young adulthood, that proportion changed to 80–90% for even arm articulations.

The outcome is unforeseen on the grounds that none of the natural models of time insight might have anticipated it. How might we decipher this outcome? Natural models of time discernment fall under two classifications: pacemaker-like neurons in the cerebrum and neurons that show a declining termination rate with time. In any case, “who” might decipher those signs in the cerebrum stays slippery.

Both model classes expect a persistent, age-subordinate, graceful progression in years. Nonetheless, this isn’t exactly what the analysts found. Overall, they discovered a shift in seen length proportions between the most youthful and the two more seasoned groups, with a defining moment at 7.How should we interpret such a predisposition inversion?

The creators called upon the idea of heuristics, presented in mental science by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman. They characterize heuristics as mental “easy routes” or “intermediaries” that empower one to pursue speedy choices. To comprehend the reason why we want heuristics for contrasting spans, let us take a gander at what else we can depend on. Since the mind has neither a dependable focal clock nor a direct, tangible plan for terms dissimilar to distances or pitches, we should utilize an intermediary.

An intermediary to “term” is something concrete yet connected with the time content, similar to “Which one might I at any point discuss?” The 5-year-old believes that if the first video was filled with activities, they could educate a lot of people.While the other film could be summed up with a solitary action word, for example, “paddling.” The significant video consisted of three episodes, an ideal illustration of a story.

The routine video, conversely, had no episodes and no storyline. As far as heuristics are concerned, the distinction can be caught by representativeness heuristics. The momentous video had more agent story models than the predictable one. Subsequently, depending on a representativeness heuristic, the kindergarteners would feel the momentous video was longer.

If this concept of span serves as a good intermediary for “time,” why do we switch to another framework at 7?The scientists contend that the response is changing to one more class of heuristics, specifically, testing heuristics. At around the age of 6 to 10, kids gain proficiency with the idea of “outright time.” We as a whole depend on the idea of outright and general time when we make arrangements, sort out our errands, and follow courses of events.

This multitude of activities supports the idea of widespread time that is autonomous of the spectator and completely reliable with Newton’s traditional mechanics. We begin considering time an actual substance, free of the occasions on which it interfaces, and we become mindful that our emotional experience of time as spectators might change or be the subject of deceptions. Everything we can manage to do to kill subjectivity is to really take a look at the progression of time.

We can actually take a look at the progression of time by habitually testing it. Taking a gander at the timekeepers or simply gazing through the window and watching the traffic stream The more often we check, the more reliable the gauge becomes.Regardless, our minds aren’t generally accessible for following time.When our attention is diverted to another task, this examination of the total time may skip cycles.Conversely, while waiting for someone who is late for an arrangement, time dials back as the mind counts the seconds while fretfulness and bothering increment.

Taking these heuristics, representativeness, and examination into account, let us see how we test the exact time when asked to determine the duration of an intriguing and dazzling video versus a wearing one out.While watching a spellbinding film, the psyche is totally drenched in the story in light of the fact that the grouping of activities unfolds so quickly that one lacks the opportunity and willpower to contemplate anything more, like life, work, or a plan for the day. All things being equal, the psyche is seized by the elective truth of the film plot.

Conversely, while watching an exhausting film, one will really look at the watch or ponder what other place one could be around then, and this large number of interruptions empowers us to test the progression of outright time. Thus, the two types of heuristics explain the strange switch around age 7 and the diligent inclination that the exhausting gatherings appear longer than they are, which remains with us until the end of our lives.

While the puzzler of time has been and will keep on captivating the human psyche, it is fundamental to understand that these central ideas, similar to existence, are more perplexing than we can nail somewhere near particular sorts of neurons in the mind. To combat such theoretical ideas, one must connect all organic and mental components. Will we ever finish that jigsaw puzzle? The truth will surface at some point.

More information: Sandra Stojić et al, Children and adults rely on different heuristics for estimation of durations, Scientific Reports (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-023-27419-4