According to two extensive studies published in 2021, the food we eat is responsible for an amazing one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions caused by human activity.

“When people talk about food systems, they always think about the cow in the field,” says statistician Francesco Tubiello, lead author of one of the studies published in Environmental Research Letters last June. True, cows contribute significantly to methane emissions, which, like other greenhouse gases, trap heat in the atmosphere. However, methane, carbon dioxide, and other greenhouse gases are released from a variety of other sources throughout the food supply chain.

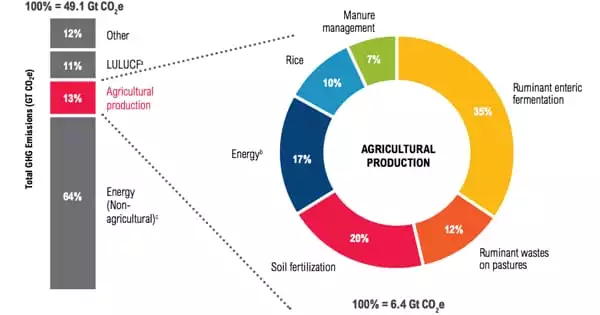

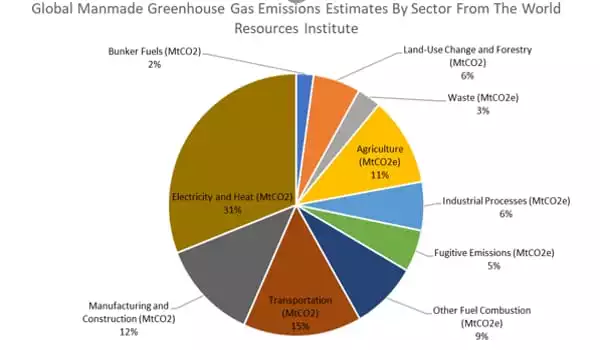

Before 2021, scientists like Tubiello of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization were well aware that agriculture and related land-use changes accounted for around 20% of the planet’s greenhouse gas emissions. Such land-use changes include clearing forests to create places for livestock grazing and pumping groundwater to flood areas for agricultural use.

However, new modeling techniques developed by Tubiello and colleagues, as well as research conducted by a group at the European Commission with whom Tubiello collaborated, revealed another significant source of emissions: the food supply chain. All the steps that take food from the farm to our plates to the landfill — transportation, processing, cooking and food waste — bring food-related emissions up from 20 percent to 33 percent.

To slow climate change, the foods we eat deserve major attention, just like fossil fuel burning, says Amos Tai, an environmental scientist at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. The fuller picture of food-related emissions demonstrates that the world needs to make drastic changes to the food system if we are to reach international goals for reducing global warming.

When people talk about food systems, they always think about the cow in the field. Cows contribute significantly to methane emissions, which, like other greenhouse gases, trap heat in the atmosphere. However, methane, carbon dioxide, and other greenhouse gases are released from a variety of other sources throughout the food supply chain.

Francesco Tubiello

Change from developing countries

Scientists have obtained a better grasp of worldwide human-related emissions in recent years because to databases such as the European Union’s EDGAR, or Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research. From 1970 to the present, the database covers every country’s human-emitting activities, from energy generation to landfill garbage. According to Monica Crippa, a scientific officer at the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre, EDGAR utilizes a consistent technique to compute emissions for all economic sectors.

Crippa’s team calculated food system emissions into four broad categories, which were published in Nature Food in March 2021: land (including agriculture and related land use changes), energy (used for producing, processing, packaging, and transporting goods), industry (including the production of chemicals used in farming and materials used to package food), and waste.

According to Crippa, the land sector is the most responsible for food system emissions, accounting for almost 70% of the global total. However, the picture differs depending on the country. Because the United States and other industrialized countries rely on highly centralized megafarms for much of their food production, the categories of energy, industry, and waste account for more than half of these countries’ food system emissions.

Agriculture and shifting land use are significantly greater contributors in emerging countries. Emissions in traditionally less developed countries have also been increasing in the last 30 years, as these countries have mowed down wild areas to make room for industrial farming and begun eating more meat, which is another big contributor to emissions with effects across all four categories.

As a result, agricultural and related landscape alterations have resulted in significant increases in food system emissions among developing countries in recent decades, whereas emissions in affluent countries have remained stable. According to the EDGAR-FOOD database, China’s food emissions increased by about 50% between 1990 and 2018, owing primarily to an increase in meat consumption. According to Tai, the average Chinese citizen ate roughly 30 grams of beef per day in 1980. In 2010, the average Chinese citizen consumed over five times as much meat, or just under 150 grams per day.

Top-emitting economies

Because of their high meat consumption, the United States and the European Union are on the list. Meat and other animal products account for the great majority of food-related emissions in the United States, according to Richard Waite, a researcher at the World Resources Institute’s food program in Washington, D.C.

In the United States, waste is also a major issue: According to a 2021 report from the United States Environmental Protection Agency, more than one-third of food produced is never consumed. Food that remains uneaten wastes the resources necessary to create, transport, and package it. Furthermore, uneaten food ends up in landfills, where it decomposes and emits methane, carbon dioxide, and other pollutants.

Meat consumption drives emissions

Climate activists who wish to reduce food emissions frequently focus on meat consumption, because animal products produce considerably more emissions than plants. Animal agriculture consumes more area than plant agriculture, and “meat production is highly inefficient,” according to Tai.

“We receive that 100 calories if we eat 100 calories of grain, like maize or soybeans,” he explains. The entire energy content of the food is transferred directly to the individual who consumes it. However, if the same amount of grain is fed to a cow or a pig, when the animal is killed and processed for food, just one-tenth of the energy from that 100 calories of grain is transferred to the individual eating the animal.

Shifting from meats to plants

Residents in the United States should investigate how they might transition to what Brent Kim refers to as “plant-forward” diets. “Plant-forward does not necessarily imply vegan.” “It means eating less animal products and eating more plant foods,” says Kim, a program officer at the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future.

The researchers revealed in 2020 in Global Environmental Change that producing the average American’s diet causes more than 2,000 kilos of greenhouse gas emissions per year. The group calculated emissions in “CO2 equivalents,” a defined quantity that allows for direct comparisons between CO2 and other greenhouse gases such as methane.