Time streams in a constant stream, yet our recollections are isolated into discrete episodes, all of which become pieces of our own story. How feelings shape this memory development process is a secret that science has, as of late, unwound. The most recent piece of information comes from UCLA clinicians, who have found that fluctuating feelings evoked by music assist with framing isolated and sturdy recollections.

The review, distributed in Nature Correspondences, utilized music to control the feelings of workers performing straightforward errands on a PC. The specialists found that the elements of individuals’ feelings shaped, in any case, nonpartisan encounters into important occasions.

“Changes in feeling evoked by music made limits between episodes that made it more straightforward for individuals to recollect what they had seen and when they had seen it,” said lead creator Bricklayer McClay, a doctoral understudy in brain science at UCLA. “We think this finding has extraordinary remedial commitment for assisting individuals with PTSD and sorrow.”

“Music-evoked changes in emotion created boundaries between episodes, making it easier for people to remember what they had seen and when they had seen it. We believe this finding has great therapeutic promise for helping people with PTSD and depression.”

Said lead author Mason McClay, a doctoral student in psychology at UCLA.

As time unfurls, individuals need to bunch data since there is a memorable lot (and not every last bit of it is valuable). Two cycles have all the earmarks of being engaged with transforming encounters into recollections over the long run: The first incorporates our recollections, compacting and connecting them into individualized episodes; the other extends and isolates every memory as the experience retreats into the past. There’s a consistent back-and-forth between incorporating recollections and isolating them, and this to-and-fro assists with framing unmistakable recollections. This adaptable cycle helps an individual comprehend and track down significance in their encounters, as well as hold data.

“It resembles placing things into boxes for long-haul stockpiling,” said creator David Clewett, an associate professor of brain research at UCLA. “At the point when we really want to recover a snippet of data, we open the container that holds it. What this examination shows is that feelings appear to be a successful box for doing this kind of association and for gaining experiences more open.”

A comparable impact might assist with making sense of why Taylor Quick’s “Times Visit” has been so compelling at making striking and enduring recollections: Her show contains significant parts that can be opened and shut to remember profoundly close-to-home encounters.

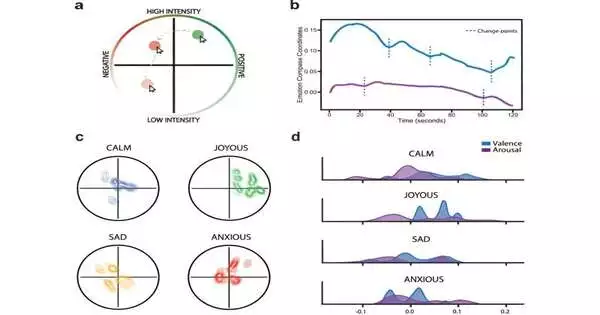

McClay and Clewett, alongside Matthew Sachs at Columbia College, employed arrangers to make music explicitly intended to inspire cheerful, restless, miserable, or quiet sensations of shifted force. Concentrate on members paying attention to the music while envisioning a story to go with a progression of impartial pictures on a PC screen, for example, a watermelon cut, a wallet, or a soccer ball. They likewise utilized the PC mouse to follow second-to-second changes in their sentiments on a clever apparatus produced for following profound responses to music.

Then, at that point, subsequent to playing out an undertaking intended to divert them, members were shown sets of pictures again in an irregular request. For each pair, they were asked which picture they had seen first and, at that point, how far separated in time they believed they had seen the two articles. Sets of items that members had seen preceding and after a difference in profound state—whether of high, low, or medium force—were recognized as having happened farther apart in time, contrasted with pictures that didn’t traverse a close-to-home change.

Members likewise had a more regrettable memory for the request for things that traversed close to home changes compared with things they had seen while in a more steady, profound state. These impacts propose that an adjustment of feeling coming about because of paying attention to music was pushing new recollections apart.

“This lets us know that extraordinary snapshots of profound change and anticipation, similar to the melodic expressions in Sovereign’s “Bohemian Song,” could be recognized as having endured longer than less emotive encounters of comparable length,” McClay said. “Performers and writers who weave close-to-home occasions together to recount a story might be instilling our recollections with a rich fleeting construction and longer feeling of time.”

The bearing of the adjustment of feeling likewise made a difference. Memory reconciliation was ideal—that is, recollections of successive things felt nearer together in time, and members were better at reviewing their requests—when the shift was toward additional good feelings. Then again, a shift toward additional pessimistic feelings (from more quiet to more troubled, for instance) would in general separate and grow the psychological distance between new recollections.

Members were additionally interviewed the next day to survey their more extended-term memory and showed better memory for things and minutes when their feelings changed, particularly assuming they were encountering extraordinary good feelings. This suggests that feeling more good and stimulated can combine various components of an encounter together in memory.

Sachs stressed the utility of music as a mediation strategy.

“Most music-put-together treatments for messes depend with respect to the way that standing by listening to music can help patients unwind or feel satisfaction, which decreases pessimistic close-to-home side effects,” he said. The advantages of music-tuning in these cases are consequently auxiliary and aberrant. Here, we are recommending a potential system by which genuinely unique music could possibly straightforwardly treat the memories that portray such problems.”

Clewett said these discoveries could assist individuals with reintegrating the recollections that have caused post-awful pressure issues.

“In the event that horrendous recollections are not put away appropriately, their items will come pouring out when the storage room entryway opens, frequently abruptly. To this end, normal occasions, like firecrackers, can set off flashbacks of horrible encounters, like enduring a bombardment or gunfire,” he said. “We want to send positive feelings, conceivably utilizing music, to assist individuals with PTSD in putting that unique memory in a crate and reintegrating it, so that gloomy feelings don’t spill over into daily existence.”

More information: Mason McClay et al. Dynamic emotional states shape the episodic structure of memory, Nature Communications (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-42241-2