Stone cells—rigid cells that prevent a nibbling insect from eating the growing branches of the Sitka spruce evergreen tree—were identified in a North Carolina State University-led study. These forest giants’ growth has been slowed by the insect’s attack.

Researchers may be able to use the new information to develop genetically enhanced Sitka spruce trees that are resistant to the spruce weevil (Pissodes strobi).

“We needed to find out about the hereditary reason for normal vermin opposition that specific Sitka tidy trees have developed to keep bugs from benefiting from the plant,” said Justin Whitehill, collaborator teacher of Christmas tree hereditary qualities at NC State and first creator of the review. Whitehill began his career as a postdoctoral scientist at the College of English and Columbia, where the research facility tests were finished.

“The quality we concentrated on in Sitka tidy is an actual protection known as stone cells, which are found in practically all plant species,” said Whitehill. “They are liable for the dirty surface you feel while eating a pear. The development of stone cells is extremely intricate and involves thousands of genes. We discovered some of the genetic factors that were involved in important initial stages of these cells’ development.”

“The trait we investigated in Sitka spruce is a physical defense known as stone cells, which are found in almost all plant species and are responsible for the gritty texture you feel when eating a pear. The growth of stone cells is extremely complicated, requiring thousands of genes. We found some of the genetics involved in the critical early phases in the formation of these cells.”

Justin Whitehill, assistant professor of Christmas tree genetics at NC State.

The Sitka tidy is an enormous conifer tree that develops on the West Coast from California to The Frozen North. Due to its vulnerability to the weevil, the tree has been replaced with other species for timber products in North America, but it is still a popular timber species in Europe. According to Whitehill, the fast-growing population of trees that grew on an island and were never exposed to the weevil made a lot of the trees grown on the West Coast for forestry products extremely susceptible.

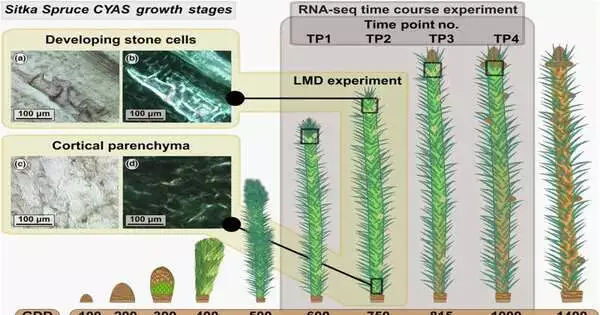

Stone cells, a rigid cell type that only grows in less than an inch of the top of budding branches—the same area where the weevil feeds—were discovered in a group of resistant Sitka spruce trees in Canada.

“The stone cells delayed the movement of the bug and gave time for the pitch tracked down in the trees’ bark to cover the bug and make it excessively tacky to take care of more,” Whitehill said. “Stone cells slow these insects down enough to prevent them from causing significant damage to the tree as they attempt to eat through the plant.

In their new review, scientists found almost 1,300 qualities that were communicated at more significant levels in stone cells. In addition, they discovered a crucial gene that acts as a “master switch” and activates thousands of other genes that control the growth of thick-walled cells in other plants.

Whitehill stated, “This paper lays out a roadmap of the genes involved in the development of stone cells.” We demonstrate that secondary cell wall genetics exert a significant influence.

A microdissection instrument that uses a laser to cut very small slices of tissue into thin sections was essential to the study conducted by the researchers. Scientists had the option to cut minuscule segments from the buds of effectively developing Sitka tidy branches to concentrate on qualities communicated explicitly in stone cells during their arrangement.

Whitehill said he has gotten financing to bring a refreshed form of this innovation to NC State. The Fraser fir tree, which is the most popular Christmas tree in the United States and is grown in western North Carolina, is currently being studied by researchers here through laser microdissection. They are utilizing this innovation to examine significant highlights that could support the practicality, scent, and vermin strength of the Fraser fir, a tree with a genome size multiple times greater than people’s.

According to Whitehill’s statement, “We’re using this approach now to look for genes involved in resistance to pathogens and pests and to understand complex ecological interactions at the genetic level.”

The paper has been accepted for publication in New Phytologist.

More information: Justin G. A. Whitehill et al, Transcriptome features of stone cell development in weevil‐resistant and susceptible Sitka spruce, New Phytologist (2023). DOI: 10.1111/nph.19103