Despite being prohibited from production for the majority of uses by the Montreal Protocol, a recent analysis found rising emissions of several ozone-depleting chemicals; a gap in the regulations is likely to blame.

The University of Bristol and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) research, which was published today in Nature Geoscience, attributes the rise in part to the chemicals, known as chlorofluorocarbons or CFCs, being used to produce other ozone-friendly alternatives to CFCs. This is an exception permitted by the Montreal Protocol, but it runs counter to its overarching objectives.

“We’re paying attention to these emissions now because of the success of the Montreal Protocol,” lead author Dr. Luke Western, a Research Fellow at the University of Bristol and scientist at NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory (GML), said. Since CFC emissions from more common uses are now prohibited, emissions from previously insignificant sources are now more closely monitored and under our radar.”.

“Their combined emissions are equal to the CO2 emissions in 2020 for a smaller developed country like Switzerland,” Western explained. This equates to around 1% of total greenhouse gas emissions in the United States.”

Lead author Dr. Luke Western, a Research Fellow at the University of Bristol.

Researchers claim that the current level of threat posed by these CFC emissions to ozone recovery is negligible. But they still have an impact on the climate because they are strong greenhouse gases.

According to Western estimates, their total emissions are comparable to those of Switzerland, a less developed nation, in 2020. According to Dr. Western, that amounts to about 1% of all greenhouse gas emissions in the US.

An international team of scientists from the US, UK, Switzerland, Australia, and Germany carried out the study.

The ozone layer that shields the Earth is known to be destroyed by CFCs. CFC production for such uses was outlawed by the Montreal Protocol in 2010; it had previously been widely used in the production of hundreds of products, including aerosol sprays, blowing agents for foams and packing materials, solvents, and in refrigeration.

The international agreement did not, however, prevent the production of CFCs during the process of other chemicals, such as hydrofluorocarbons, or HFCs, which were created as second-generation CFCs. substitutes.

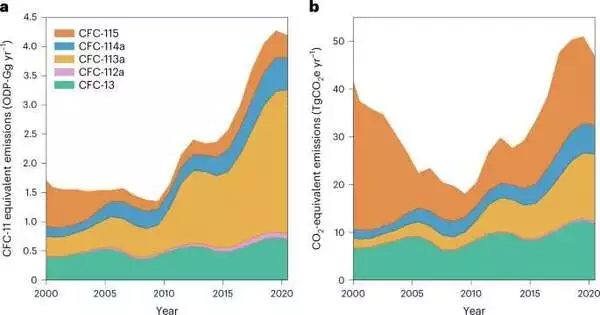

CFC-13, CFC-112a, CFC-113a, CFC-114a, and CFC-115 were the five CFCs that were the focus of this study. Their atmospheric lifetimes range from 52 to 640 years, and they are known to have few or no known current uses. These emissions, which had a similar effect on the ozone layer as a recent rise in emissions of CFC-11, a substance regulated by the Montreal Protocol and thought to be the result of hidden new production, were about one-fourth of that increase.

The researchers used data from the Advanced Global Atmospheric Gas Experiment (AGAGE), in which the University of Bristol plays a key role, as well as data from the University of East Anglia, the Forschungszentrum Jülich, and NOAA in the US. These were combined with an atmospheric transport model to demonstrate that after the production of these CFCs for the majority of uses was phased out in 2010, their abundances and emissions increased globally.

The study’s three CFCs, CFC-113a, CFC-114a, and CFC-115, showed that their production of two common HFCs, which are primarily used in air conditioning and refrigeration, may have contributed to the increased emissions. Less is known about the causes of the rise in CFC-13 and CFC-112a emissions.

The team discovered rising global emissions but was unable to pinpoint any specific areas.

According to study co-author Dr. Johannes Laube of the Institute of Energy and Climate Research (IEK) at Forschungszentrum Jülich, “given the continued rise of these chemicals in the atmosphere, perhaps it is time to think about sharpening the Montreal Protocol a bit more.”

Researchers claim that some of the advantages of the Montreal Protocol may be reversed if emissions of these five CFCs keep increasing. The study noted that by reducing leakages connected to HFC production and properly destroying any co-produced CFCs, these emissions might be minimized or prevented.

Dr. “The key takeaway is that some of the CFC-replacement chemicals’ production processes may not be entirely ozone-friendly, even if the replacement chemicals themselves are,” Western said in his conclusion.

More information: Luke Western, Global increase of ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons from 2010 to 2020, Nature Geoscience (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41561-023-01147-w. www.nature.com/articles/s41561-023-01147-w