A study by experts from the UPF Culture, Paleontology, and Socio-Environmental Elements Exploration Gathering (CaSEs), recently published in the journal PLOS ONE, provides a global evaluation of traditional limited scope cultivating practices for three of the world’s most significant dry spell tolerant species: finger millet, pearl millet, and sorghum.

The exploration, which joins previously distributed ethnographic information and new data gathered in the field, exhibits how customary, limited-scope rainfed horticulture gives novel data on feasible farming practices at the convergence of conventional natural information and scholastic information.

According to Isabel Ruiz Giralt, “Our work propels how we might interpret how human networks created maintainable and strong agrarian techniques over the long run.” This is especially significant in the current context of environmental instability and population growth, which necessitates quick action.

“Our research contributes to a better understanding of how human populations evolved sustainable and resilient farming techniques across time. This is especially important in light of the current climate instability and population expansion, which necessitates quick response.”

Abel Ruiz Giralt

Finger millet, pearl millet, and sorghum are essential staple harvests in drylands, and their creation dates back over 5,000 years. Be that as it may, compared with different harvests, the development of millet and sorghum has logically diminished over the most recent 50 years.

In the midst of global environmental change and rising levels of aridity, an examination of nearby practices and traditional harvests is critical.Customary natural information gives a vital wellspring of data, since it envelops the double-dealing of locally accessible assets, and is the consequence of cycles of long haul transformation to the climate.

“Our work propels how we might interpret how human networks created maintainable and strong rural techniques over the long haul.” This is especially important in the ebb-and-flow setting of environmental instability and population development, which necessitates quick action,” says Abel Ruiz-Giralt, the article’s first author, along with Marco Madella, Stefano Biagetti, and Carla Lancelotti, all analysts at the UPF Division of Humanities, and members of the CaSEs Exploration Gathering.

The writers note that customary practices to increase crop yields depend on sustainable assets, in opposition to the far-reaching and momentary arrangements frequently utilized by supranational foundations, which cause huge harm to both harvest biodiversity and soil preservation.

These customary practices empower expanding efficiency and limiting harvest disappointment without forfeiting long-haul supportability and flexibility. “Our review offers an elective view on potential ways of coordinating customary information into logical and political projects, determined to give answers for food security in low- and middle-income bone-dry regions,” the specialists say.

Making new models to make sense of conventional cultivating rehearsals

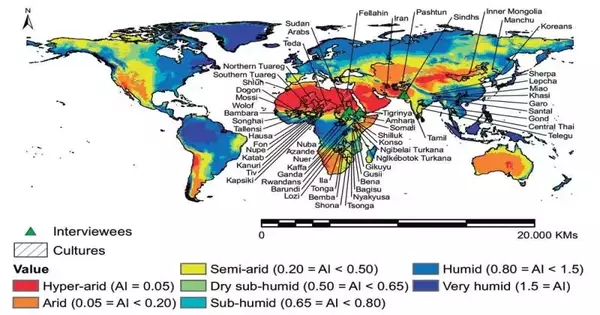

In their exploration, the creators construct and test models that show the connection of biological and geographic factors, which effectively make sense of conventional farming practices and the fluctuation of existing frameworks in this field, as well as planning the conceivable development areas of finger millet, pearl millet, and sorghum on a worldwide level.

“We have tracked down that the connection between complete yearly precipitation and the reasonability and fluctuation of horticultural frameworks in drylands all over the planet isn’t generally a major area of strength, as was recently thought.” “Different factors, for example, the length of development cycles, the accessibility of soil supplements, and the water maintenance limit appear to be undeniably more determinant in the configuration of traditional agro-biological systems,” they write.

The scientists have decided to utilize a similar worldwide methodology, which permits improving on complex ethnographic information since they have diminished intracultural inconstancy through speculations in light of the most well-known rehearsals. Thus, they have utilized the ethnographic information accessible in the eHRAF World Societies data set as the fundamental wellspring of data.

“We have tracked down that the connection between absolute yearly precipitation and the feasibility and changeability of agrarian frameworks in drylands all over the planet isn’t quite as serious an area of strength as was recently suspected.”

The eHRAF World Societies data set contains countless archives that depict exercises obtained from customary environmental information (TEK) from around the world, information that comes from ethnographic investigations completed unevenly during the most recent two centuries.

“Regardless of the unavoidable twisting created by the utilization of information gathered under various hypothetical and systemic viewpoints over 150 years of ethnographic examination, the eHRAF data set keeps on being one of the best instruments for directing worldwide ethnographic research because of the abundance of data it supplies,” Abel Ruiz-Giralt says.

The models introduced in the review, which use different natural indicators for their plans, work on the connections and associations among people and the climate and can consequently be valuable to comprehend the fundamental general elements engaged with the review and advancement of customary farming frameworks. “We accept our paper as a convenient and important commitment to this discussion, as it gives new information on smallholder agriculture at the crossing point of conventional environmental and scholarly information.”

More information: Abel Ruiz-Giralt et al, Small-scale farming in drylands: New models for resilient practices of millet and sorghum cultivation, PLOS ONE (2023). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0268120